An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 75 (of 95 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 25

‘Memories of Clock Face Colliery’ by Keith Longworth

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

‘Memories of Clock Face Colliery’ by Keith Longworth

‘Memories of Clock Face Colliery’ by Keith Longworth

I finished my education at Windleshaw Primary School, which was a poor excuse as a place of learning. Between the ages of 11 and 12 I had attended the Central Modern Secondary School but the parish priest at St Joseph’s in Peasley Cross harangued my mother to return me to a good Catholic school. The result was no more algebra, French, art, ancient and also modern European history. Actually my education ceased from that point on. Anyway I left school in 1953 and within a week was undergoing training to become a miner.

The mine where we did most of our training was Lyme Pit near Haydock. There I became familiar with working underground and learning the skills needed to be productive, once I had been allocated a colliery to work at. During our initial training we also attended the Mining School in Corporation Street for one day a week. Because I wished to be more than just a coal miner, I wanted to learn about Mining Law and Mining Science with a view to one day becoming either a Mine Manager or Mining Engineer. At the time I entered the mining industry, coal mining was ‘king’, with a future of at least 100 years. At least that’s what we were told!

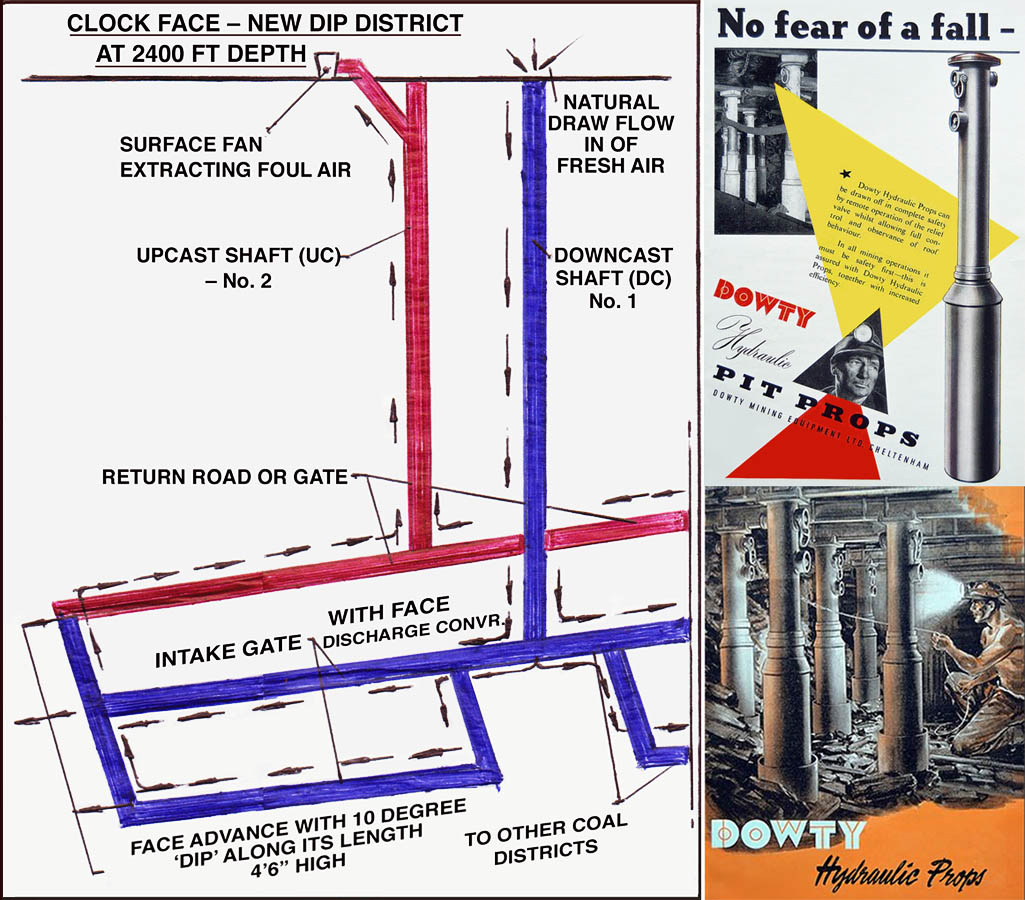

On completing my training I was allocated a place at Clock Face Colliery where my father was a deputy and where my two older brothers worked underground. Clock Face was split up into districts underground and the one I worked in was called the ‘New Dip’. This was very aptly named as it was certainly on a dip of over 10 degrees. The coal seam was about 4ft 6 inches high and its configuration was a Long Wall system, with the coal face being about 80 to 100 yards long. At the highest end there was an air intake drive, with a production belt drive in the centre and a return drive at the lower end.

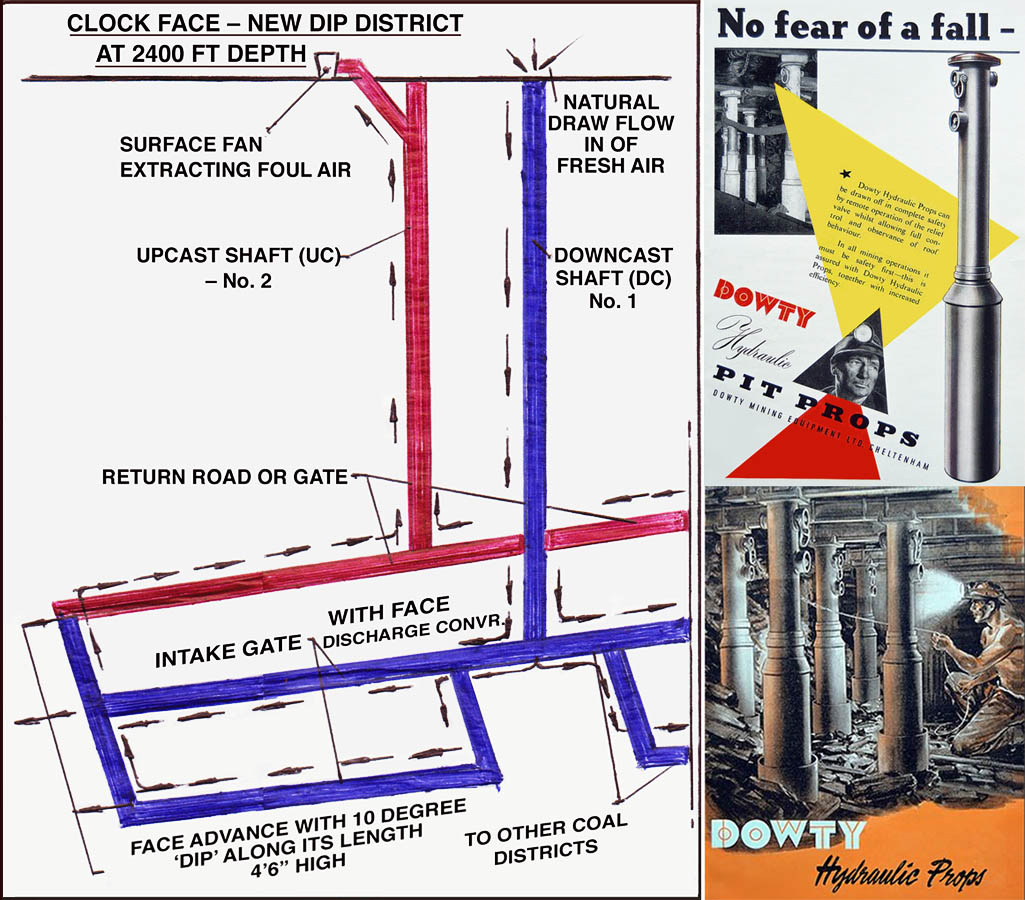

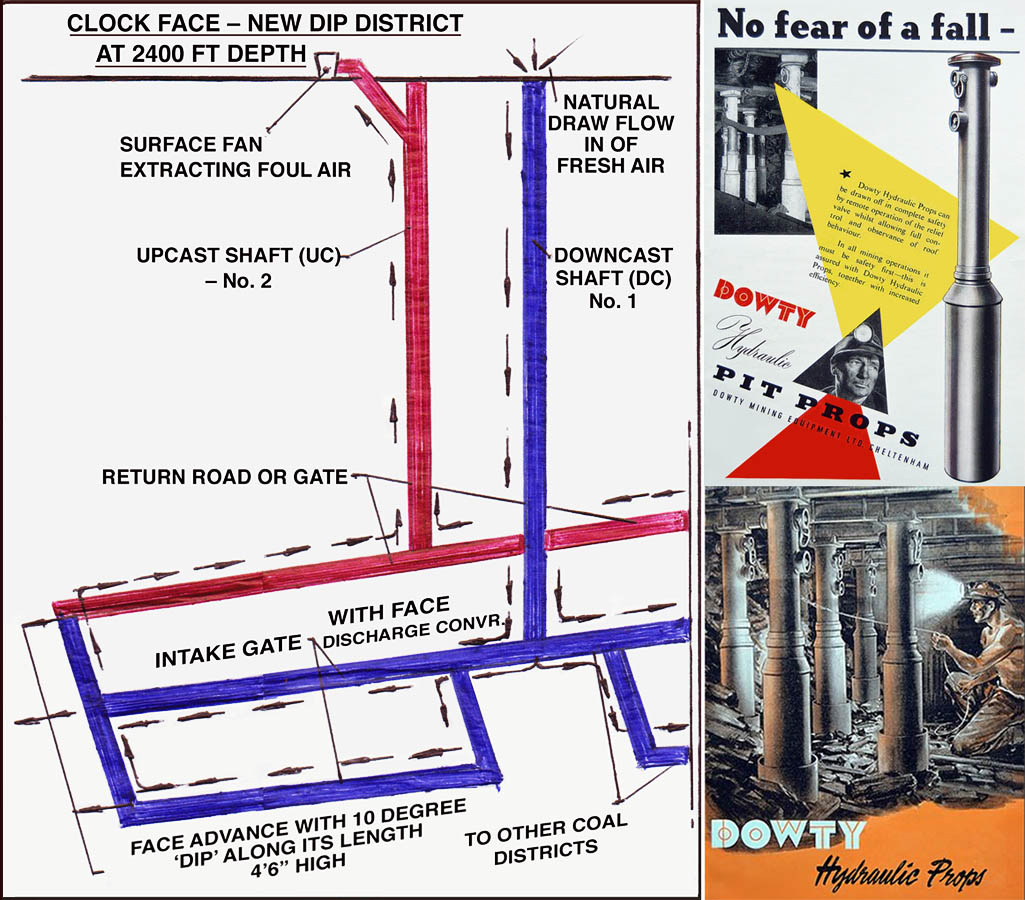

Left: Air flow diagram by Harry Hickson of the Clock Face Colliery New Dip district; Right: Dowty hydraulic props

Air flow diagram of the New Dip district and Dowty hydraulic props

New Dip district and Dowty props

In order to earn extra money I used to pick up the powder and detonators from the magazine area, which was situated well away from the mine shafts. I also undertook training as a first aid officer at the Clock Face Social Club on a Monday night until I qualified after 6 months tuition. So I also carried first aid equipment, which was basically in a pannikin strapped to my belt. So as you can see I was determined to make a career out of mining.

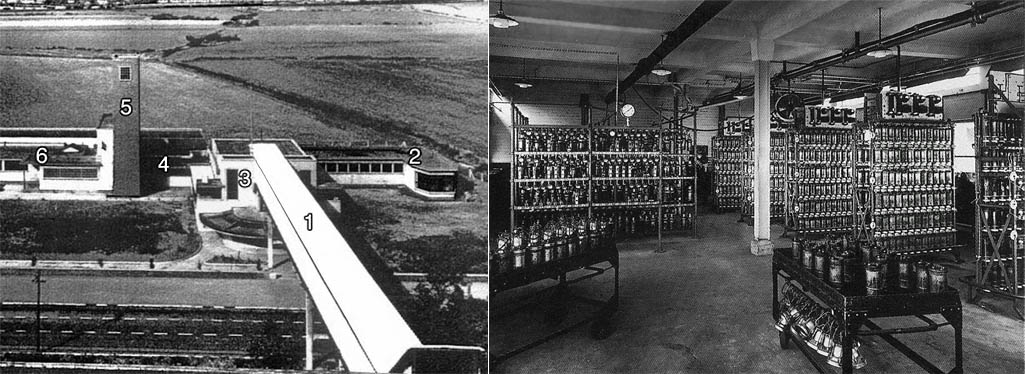

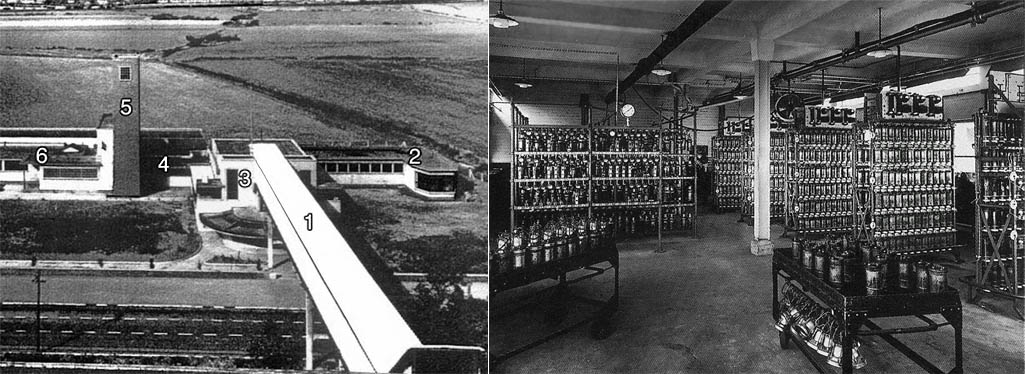

Left: 1) Walkway; 2) Shower area; 3) Lamp room; 4) Locker room; 5) Water tower; 6) Canteen. Right: Clock Face Colliery Lamp Room

1) Walkway; 2) Showers; 3) Lamp room; 4) Lockers; 5) Water tower; 6) Canteen. Right: Lamp Room

Clock Face Colliery Lamp Room

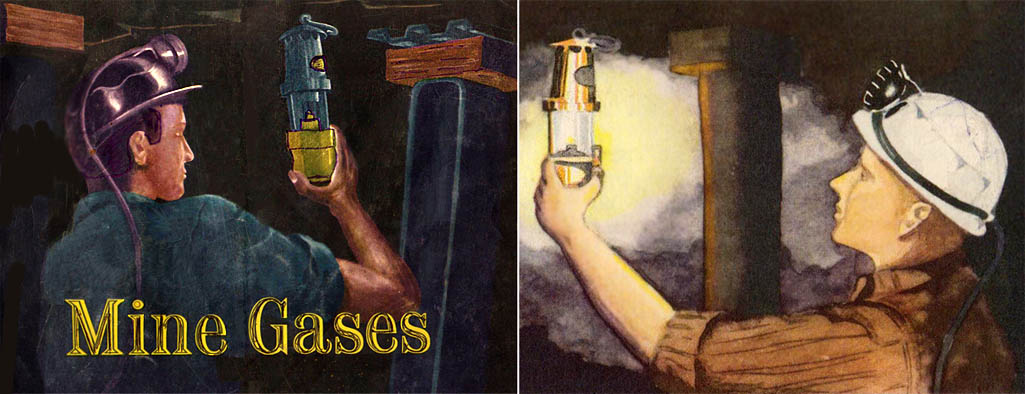

The National Coal Board’s Mine Gases booklet which was issued to students at the NCB’s training schools

Mine Gases booklet issued to students at the NCB’s training schools

This booklet was issued to students at the NCB’s training schools

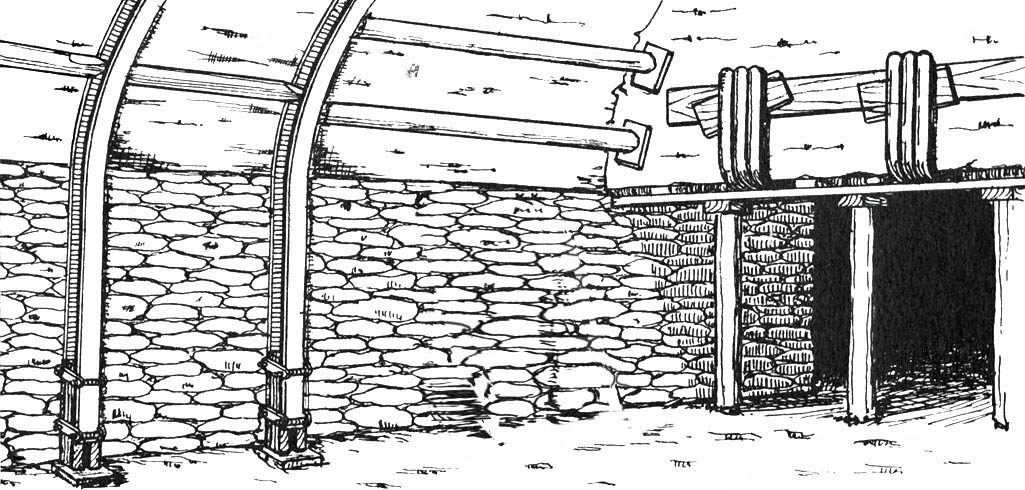

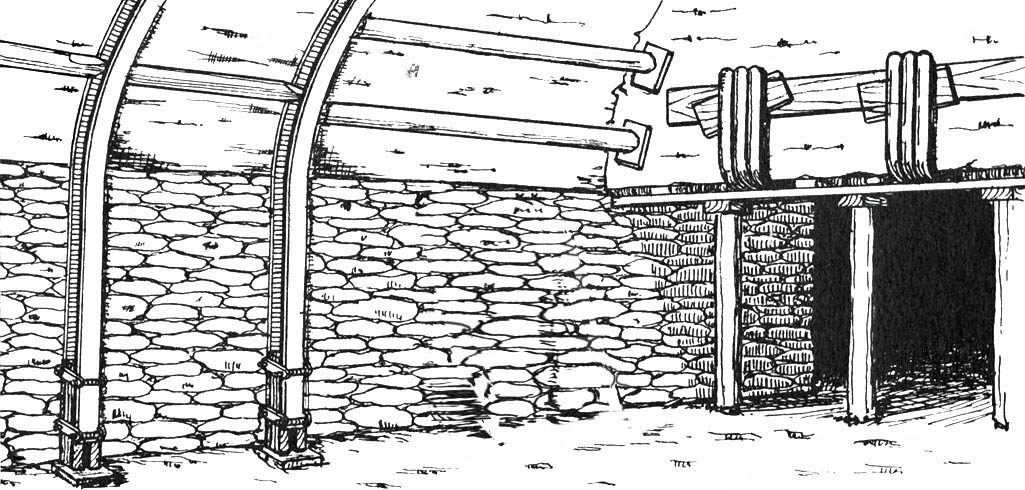

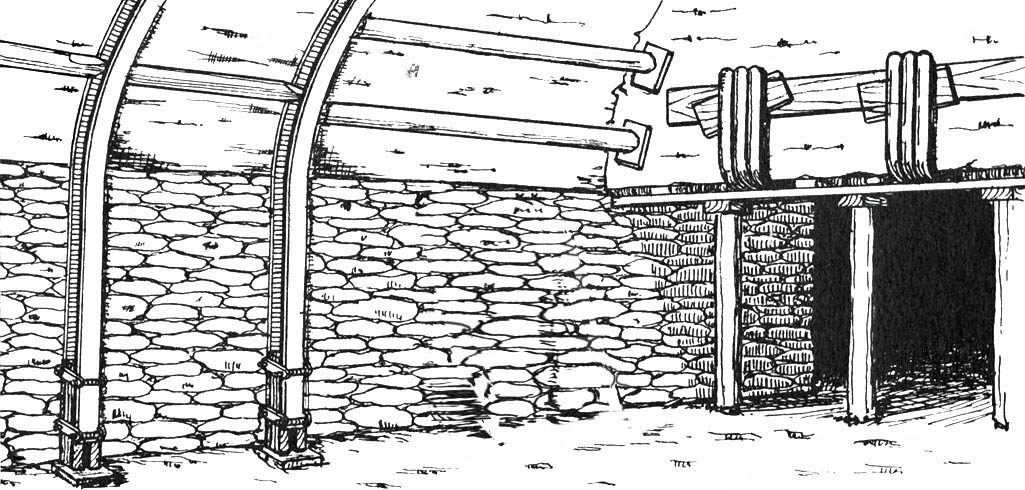

Because we were extracting the coal on a continuous basis, we had an on-going problem of keeping the pit roof well-supported. To help support the roof miners who were employed as packers used to construct packs of rock. They used to be paid according to the size pack they constructed, generally by the linear yard. Where the previous coal extraction had taken place was called the waste or the gob.

Roadway heading showing an example of a stone pack to support the roof, a top rated method of permanent support

Roadway heading showing an example of a stone pack to support the roof

Stone pack supporting a pit roof

As you can see it was a pretty hairy sort of workplace, even without the roof collapsing or having to control incoming water, as sometimes happened. My main memory of underground mining was constant dust, unabated noise (unless there was a breakdown) and cramped conditions. Sometimes on a weekend when I was in the countryside, maybe at Billinge overlooking St Helens with its ever-present smoke stacks at Pilks and Ravenhead’s stuff rook (waste dump), I used to think about Dante’s Inferno. And when I was down the mine I knew I was in it, in the bowels of the earth!

Because I was studying whilst working at Clock Face I would only work the day shift. So I would be at the pit head at the time when they stopped winding off the coal and we were able to descend. This was just after 6am and then we would return to the surface from 2pm onwards. Sometimes we were required to stay on for a couple of extra hours, so we would only resurface after 4pm. That meant in winter you went underground before daylight and returned to the surface at dusk. At the end of one winter I got a skin complaint where I lost most of my skin. Initially the medical officers (doctors) thought it was rheumatic fever but on further investigation decided it was a result of a lack of sunlight or vitamin D. After the initial shock I decided that maybe a career in mining wasn’t for me.

Mining must have been the unhealthiest occupation anyone could have undertaken. My father died in his early fifties along with two other brothers of either silicosis or pneumoconiosis related conditions. But because they hadn’t had X-rays whilst still alive, their widows didn’t qualify for ex-gratia payment from the coal board. Only one, my uncle, survived to the age of 70. The day after my father died my mother lost her eligibility for the 1 tonne miners’ coal allowance, even though at the time my two older brothers were working underground at Clock Face. The reason given was that they were not registered householders. My father had been a miner from the age of 14 until he died at age of 53 in 1957.

Anyway to get back to my initial description of mining in the early ‘50s. It was a constant battle to maintain the integrity of the drives to the coal face because of the reaction of the strata above the coal seam to close the gap where the coal had been. All the overburden area above the seam would be sedimentary rock, which fractures easily and therefore is very unstable and dangerous, prone to collapsing without warning and on occasion with fatal results. Along with these natural hazards, there was always some that were generated by human carelessness. For example, placing powder behind support rings and also the unnecessary detonation of detonators to save the officers from making a trip to return them to the magazine store on the surface.

All told it was a very dangerous occupation, which gladly has ceased in the Lancashire coalfields. When I did Mining Science the lecturers constantly reminded us that the worst thing you can do with coal is burn it! And here we are over 60 years after we were told and still burning it. Monty Python is nothing on reality!