An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 61 (of 95 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 11

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

'Memories of My Father's Work at Sutton Oak & Nancecuke' by John Hunter

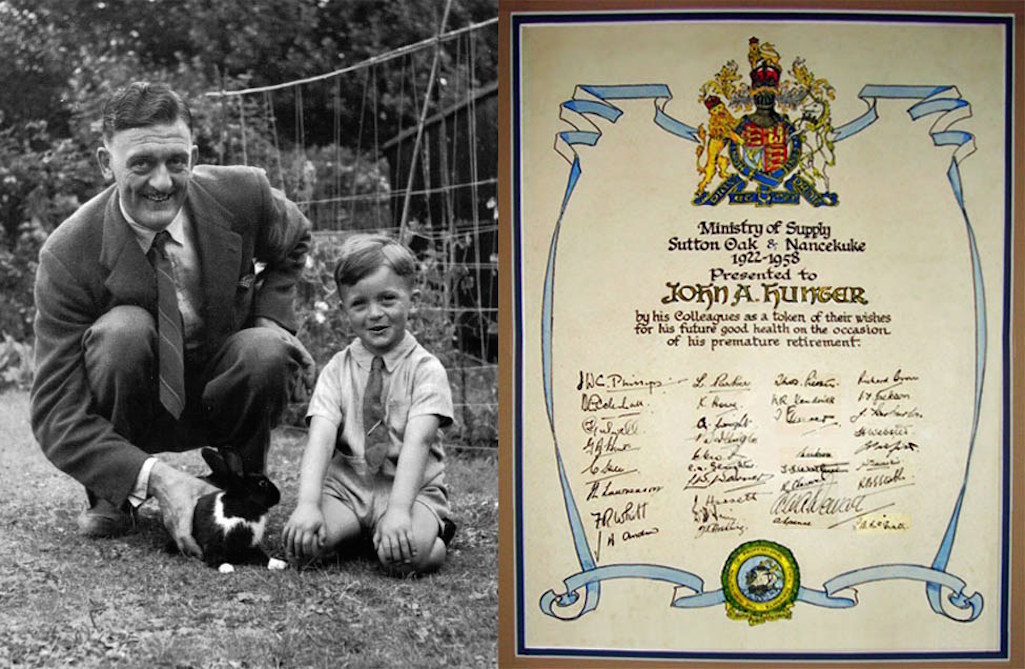

My father was John Alexander Hunter who was born on September 17th 1902 in Eccleston, St.Helens. He worked at the Sutton Oak mustard gas plant for almost thirty years, from 1922 to 1951. I was born in 1940 and the only occasion I visited the plant with my father was at Christmas 1947 or 1948. It was a small Christmas party for children and I remember seeing a uniformed security guard armed with what looked like a Colt 38 revolver. We lived at 45 Brookside Avenue, Eccleston and I believe my father purchased this semi-detached house in 1933 for the sum of £240. I do recall that he had regular visits at home by Dr Ferry, a government doctor, to treat his emphysema caused by mustard gas poisoning.

John Hunter Snr. & Jnr. in Brookside Avenue in 1944 and a plaque presented to John Hunter in 1958

John Hunter Snr. & Jnr. and plaque presented to John Hunter in 1958

John Hunter Snr. & Jnr. and a plaque presented to John Hunter in 1958

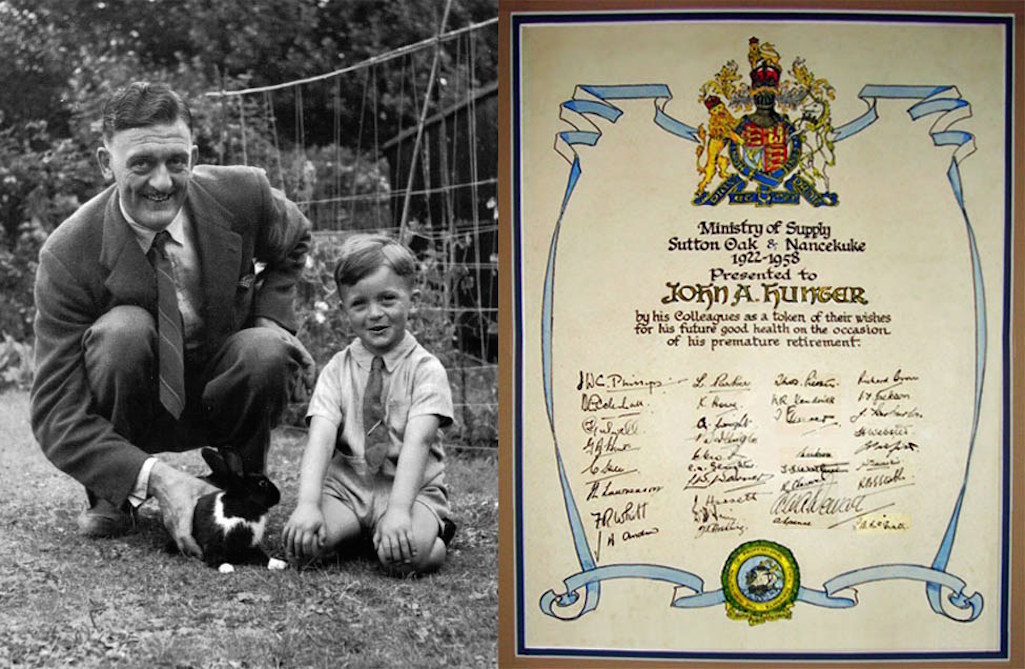

I have possession of a book which my father left to me after his passing. It's titled 'Chemical Warfare' by Curt Wachtel. The inside cover has a stamp which says C.D.R.E / Sutton Oak Library and Records Section and it gives all the formulas and toxic effects for various compounds used in WW1. In closing, I should mention that my father lived many years longer than what Dr Ferry had told my mother. Cora Hunter was a nurse at both Liverpool General and Alder Hey hospitals and so she understood father’s condition. He died in in 1978 aged 76.

'Memories of the Poison Gas Works' by Stan Bate

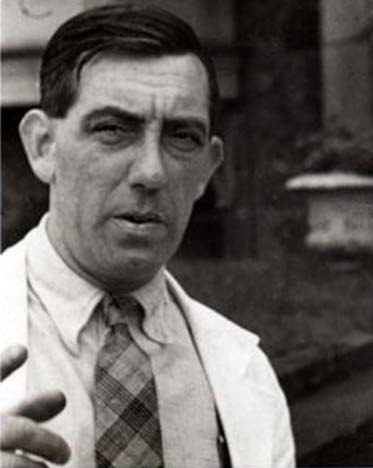

This is a personal account of an air accident as told to me by my father, James Bate. During the 1930s he worked in Roughdale’s Quarry, in Chester Lane and he's pictured below with a colleague, holding a pick. During the second world war he was a Fireman at HM Chemical Defence & Research Factory, Reginald Road, Sutton Oak, known locally as ‘The Poison Gas Works’ or 'Magnum'. In an effort to effectively minimise the risk of a major fire, resulting in a possible discharge of gas, the factory had its own fire fighting equipment and employed its own Firemen.

James Bate on the right working in Roughdales Quarry during the 1930s - contributed by Stan Bate

James Bate on the right working in Roughdales Quarry during the 1930s

James Bate on the right working in Roughdales Quarry during the 1930s

On hearing of the crash the Firemen at the factory were preparing to turn out and attend, using their portable pumps, but were stopped from doing so by their senior officers and management because there were so many employees running from their places of work to observe the accident, leaving the factory vulnerable to possible fire and explosion. The firemen, with their exceptional knowledge of the area and its emergency water sources, would have been at the scene long before the local Auxiliary Fire Service, one of whose engines went into a ditch, however, nothing could have been done to save the victims. Anyone who has seen images of soldiers in the First Word War, clearly suffering from the effects of a poison gas attack, can only imagine what would have happen to the people of Sutton if that bomber had stayed airborne for an extra two or three seconds and crashed into the factory; the result would have been catastrophic.

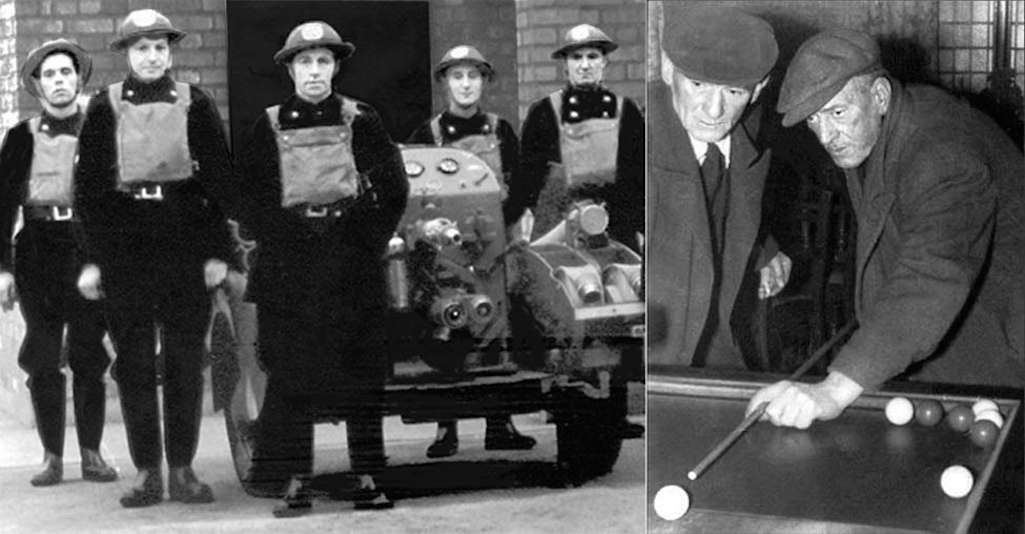

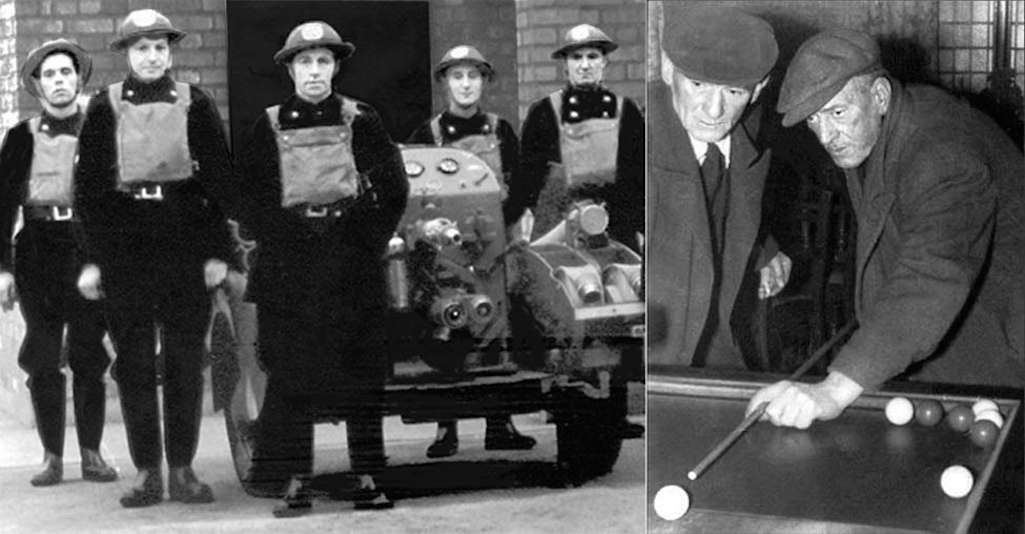

James Bate at far right of this group of firemen at the poison gas works. Right James (left) in later years in the Mill House

Fireman James Bate (on the far right) and in later years in the Mill House

Fireman James Bate on the far right

Early in the 1990s, a small factory producing brass castings was being built on the site. As the builders began digging out the foundations they came across what can only be described as six very large cauldrons, complete with lids. They were obviously some kind of pressure vessel, whose dimensions where approximately seven feet from base to rim, six feet six in diameter and three inches thick; the lids were dome shaped and attached to the base with large bolts around the rim.

Over the following years I became very friendly with the factory owner who one day told me that apart from the cauldrons, further excavation of the site had also turned up some other very sinister finds such as thousands of boxes of glass vials containing small amounts of liquid poison gas. I understand that they were to be used by operatives within the factory who, on suspecting a gas leak, would break open the vial and sniff its contents in an attempt to identify the category of gas escaping into the atmosphere; a WW2 anti aircraft gun was also extracted.

I was informed by the factory owner that all this toxic waste had to be transported to the south of England for disposal by a specialist company, at a cost of many thousands of pounds to his company. When he approached the local Council, who gave planning permission for the factory, and the government regarding reimbursement for his outlay, they refused to confirm that a poison gas factory had ever been on that site. However, one day a delegation of officials, made up from a number of countries around the world, arrived at the factory, escorted by armed police. It is understood that they had come on behalf of the United Nations, to ensure that poison gas was no longer being produced on the site.

Their undeclared arrival at the factory was due to a non-proliferation treaty agreement between the western powers and Russia, following which the government had to own up to the factories existence as it was on a list of defunct establishments that were open to examination by the signatories, and it had to be shown to have been fully decommissioned. Only after this admission by the government was the factory owner able to recover his outlay for disposing of the toxic waste.

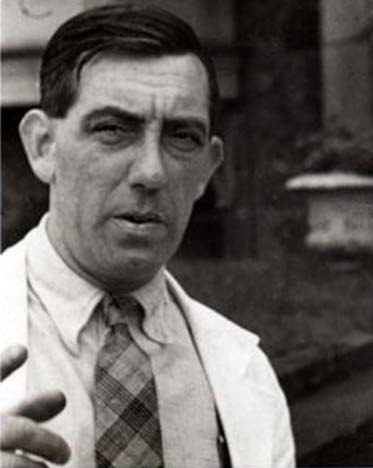

'Ernest Booth Research Organic Chemist' by Elisabeth Nicolson

Ernest Booth, my late father, worked as a research chemist at Sutton Oak Chemical Defence Research Establishment in St Helens, Lancashire, at the time of my birth, on Sunday 14.03.1943, in St Helens Hospital, UD. This I know, as it is written on my birth certificate under the column 'Rank and Profession of father' as 'Research Chemist, HM Factory, St Helens'. In the manner of his generation, and as I now understand it, under the terms of the Official Secrets Act, Dad said very little about this part of his life (or about any other part of his life, for that matter!!). It is perhaps time for me to ask my three younger brothers, John, Donald and Steven William, what they learned from Dad. We lived at 84, St Helens Road, Rainford at this time. The owners had gone to Canada 'for the duration of hostilities', locking their belongings in to some of the rooms.

Left: Ernest Booth (1911-86) with daughter Elisabeth at the 'pig-farm' near their St.Helens Road home in 1944

Right: at the Institute of Seaweed Research at Inveresk, Musselburgh, East Lothian - contributed by Lis Nicolson

Ernest Booth with Elisabeth in 1944 and at the Institute of Seaweed Research

Ernest Booth with daughter Elisabeth

Research at Inveresk - contributed by Lis Nicolson

Having recently read about lung damage among workers at Sutton Oak, only now do I realise that Dad had a shocking early morning cough, and years later, he coughed up some blood, which caused a stir in the family at the time (he smoked like a chimney, on a pipe). Upon broncoscopy, the doctors discovered what they called 'old lung damage'. Dad told them that he had had a very bad dose of whooping cough when we, his children, did, at which time he would have been about 37. The doctors agreed that this damage was consistent with this clinical history. But Sutton Oak was never thought of until I write this now.

As the War came to an end, the owners of 84, St Helens Road, Rainford came back from Canada to their house, and Mum, Dad and I went to live with Mum's parents, John and Marion Marjorie Tyldesley at 4 Leinster Road, Swinton. Dad worked for Hardman and Holden, possibly somewhere in Salford, at this time. They made, among other things, Rennies indigestion lozenges, which he told us children were 'just the same thing as blackboard chalk!!' They were having a house built for us in Cheadle Hulme. But neither men nor materials were readily available, and we finally moved there in 1947. Dad, by this time, was Works Manager for British Schering, in Hazel Grove. I understand that they were pioneering research into synthetic sex hormones. This led to the advent of THE PILL!!!

My understanding is that Dr Neville Woodward at the Institute of Seaweed Research and who had been Dad's boss at Sutton Oak, invited him to apply for the job at the Institute at Inveresk, Musselburgh, Midlothian (now East Lothian). When Dad's job finally came to an end, he moved back to Rawtenstall and Calico Printing at Broad Oak Mill, Accrington. This mill would seem to have had a historic place in textiles. Then finally, the mill closed and Dad became a Consultant. This took him all around seaweedy places including twelve months with the United Nations, doing a world tour, to promote sales of seaweed products, as I understand it. The only continent he did not visit was Australasia.

His very last job was to design a liquid seaweed manure plant in Tralee, Co Kerry, Ireland. Alas, while recovering from minor surgery, (in the War Memorial Hospital, Lytham St Annes) and between his meat-course and his pudding, he collapsed and died! This was in 1986 and he had become a world expert on seaweed, lecturing at various International Seaweed Symposiums/a, held every four years, always in seaside university cities. Some of his papers are on the internet, and I have some, here, too. I have also visited the factory in Tralee, where the owner, Dr Henry Lyons, told me how much they had wished that Dad could have lived a little longer, to help them with their early 'teething problems' at the factory.

Ernest Booth pictured at the Institute of Seaweed Research at Inveresk