An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 85 (of 95 parts) - Mineworking in Sutton, St.Helens

Researched and Written by Stephen Wainwright & Harry Hickson ©MMXX Contact

Sutton Manor Colliery | Bold Colliery

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

Mineworking was first recorded in Sutton Heath as early as 1540 with a seam of coal accidentally discovered by members of the Eltonhead family while digging a clay pit. As they were tenants on the Bold estate, this led to a lengthy dispute until the Eltonheads agreed to pay their landlord, Richard Bold, a commission on the coal extracted from his land. The Bolds themselves soon got in on the act and a number of new shafts were dug to the chagrin of the people of Sutton. Documents from about 1588 reveal residents highly critical of the mining operations of Richard Bold and record how mining had made walking in Sutton rather precarious. One said:

Believed to be the earliest illustration of coal mining activity in Lancashire which refers to ‘Pembtons coal myne’

The earliest illustration of coal mining activity in Lancashire

Earliest illustration of Lancashire mining

These latest records were almost 200 hundred years before the introduction of the steam engine development needed to work deeper mines that we do have records for. So the question is what type of mining was carried out in the mid 1500s and how did it develop? Understanding what is meant by these records and more importantly, how Sutton's coal mining history developed, requires us to examine the impact of the key element of mining, which is the geology of the earth in the area. Most of the earth’s strata (i.e. layers) containing coal were horizontal when formed but over millions of years of evolution tremendous forces made significant changes to the strata form.

The coal seam strata in the Lancashire Coal Fields, unlike those in the Midlands, has not been kind to mining companies. They had to cope with many challenges that these strata changes created and which was on-going, causing constant roof and floor buckling. It is not intended for this page to cover all of the geology conditions that took place in these periods of evolution; however a few basic ones will illustrate those which did influence the viability of coal mining and made the study of geology such an integral part of mine managers / engineers professional qualifications.

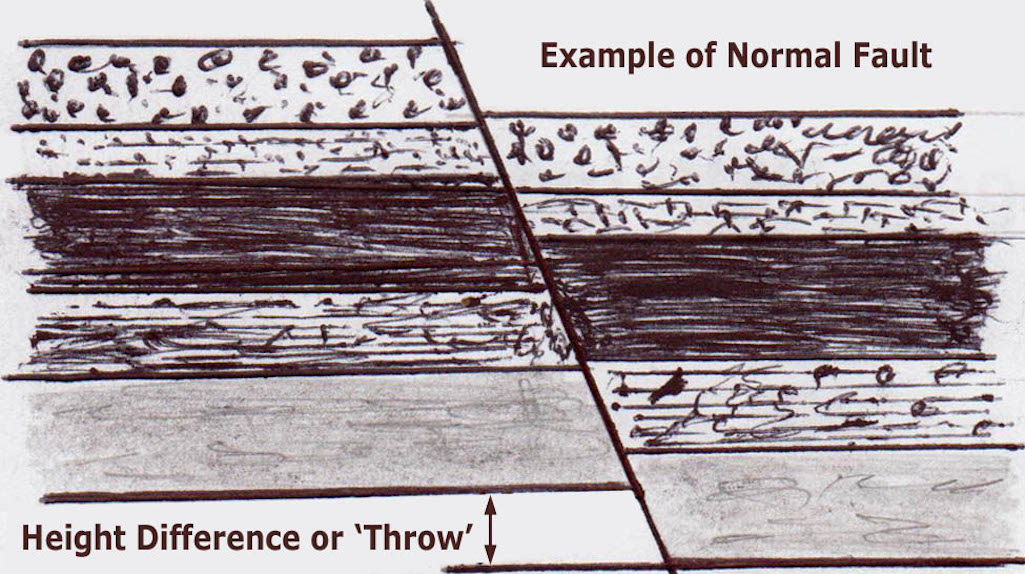

The Sutton Heath, Thatto Heath, Prescot Road area is of an appreciably higher elevation than Sutton itself, a feature caused by a significant upward force over millions of years of evolution. This created, for example, the major fault that passes through Croppers Hill on Prescot Road, a line that forms the northern limits of the old Sutton Township boundary. A fault in the earth's strata is where tremendous pressures have led to it being broken, producing a crack with height difference on either side, which could potentially be up to hundreds of feet. There are many other types of faults far too numerous to cover here, although references are made in the Bold and Sutton Manor Colliery pages of major faults that seriously impacted on their full utilisation of coal reserves and which required high, expensive technology to overcome.

One final important but interesting fact of geology relative to mining is that of the strata temperature. The strata temperature in the Sutton mines at a depth of 50 feet is roughly constant at about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. However it increases by 1 degree for every 60 feet below that point. This means that the No. 2 shaft bottom temperature at the later Sutton Manor Colliery would naturally be about 88 degrees. When the further depths of coal seam dip are added towards the coal faces – as well as the possible slow oxidation temperature of the coal measures – it can be appreciated that working conditions can be very hot and humid requiring good ventilation. Thankfully in these early days of mining the depths didn't produce those sorts of temperature.

The early 1500s mining described above was at locations where the higher level coal seams had been pushed up and exposed as surface outcrops. Initially these just required removing by pick and shovel, basically being the early opencast mining approach. In locations where clay pits had been dug or stone / slate quarrying had taken place, it soon became evident that if an adjoining coal seam could be seen in the strata, it would be dipping down at a certain angle. In order to keep working the mine, any shafts already dug would need to go deeper to reach that coal. This knowledge led to the very first method of underground mining, known as Bell Pit Mining, which had started in England around 1300.

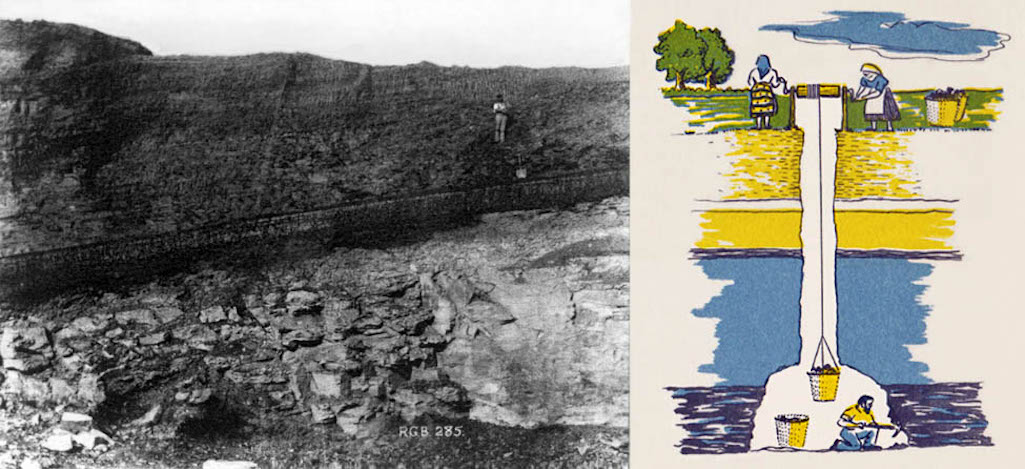

Bell Pit Mining was carried out by first manually digging a hole down to the coal seam and the coal removed by digging it out in the form of a bell chamber. The reason for this is that with the slow depletion of available timber to support the roof, the arch of the bell would be the strongest natural shape to minimise the collapse of the workplace. Into these pits the miner would descend via a rope lowered by a simple hand-winch pulley, which a couple of people would work. These would also wind up the coal contained within a basic rush basket that the miner filled.

Whilst the basic method of bringing the coal up appears very simple, fatal accidents did happen. This might be when the basket reached the surface and the worker reached out to pull the basket clear of the shaft and then overbalanced. These early Bell pits were only up to about 25 feet deep, with a limit to the size of the excavation of the chamber largely dictated by the strata geology at that point. Some of the other problems that were faced by the miner were that there was very little ventilation, gas in various forms could be released, he was working with a very basic tallow candle light, stones from within the shaft would be dislodged and being completely open, the chamber would be flooded at times by heavy rain.

When flooding or a complete collapse of the roof occurred or the complete extraction of the coal from within the chamber, the pit would be abandoned and a new shaft close by dug in the coal seam. The result of this was that eventually the whole area would be dotted with abandoned pits, mostly full of water, which created the conditions that the local residents were vocally complaining about in the record above. It is almost certain that the aforementioned Pembton mines would have been worked by this Bell pit method. Whilst it is easy to say now how improvements could then have been made, the available markets have always dictated the evolution of mining, and how much pit owners were willing to pay for their operations.

We know from records from the nearby Peasley Cross Colliery (which was located where the later UGB factory was), that the Fiery seam there was 2 feet 2 inches, and in the photograph this appears to be similar. The dip of these strata is approximately 1 in 7, which in general was a common dip for Sutton mines, but this of course varied throughout the many collieries, as has been said. Juxtaposed with the photograph is a sketch of the typical basic Bell mine technique of hand winding, with the miner shown in the Bell chamber.

The next development method in some English Bell mining records from about 1650, was to have two shafts in operation close together, although not being connected. This is believed to have resulted from miners finding the ventilation in one shaft was passing through the pervious strata structure into the other. This simple development resulted in a significant increase in the potential depth of the shaft because the improved ventilation diluted any gas within the chamber. Obviously with any increase in depth, an improved system of winding was required and this led to the use of a horse walking around in a circle turning the winding drum through a system of ‘cogs and wheels’.

The final development in the Bell Pit story came approximately around the early 1700s with the invention of the steam engines that were used to pump water out of the mine. This in turn was used to drive a water wheel connected to the winding drum. Bell mining although very basic, was, however, a very important period of mining history for Sutton because it provided much valuable information that was used in the economic development of the next stage of coal mining.

Only a few years later the progressive development of local and international trade, canals and railways, together with the Industrial Revolution, brought about increased mechanical invention, with opportunities to establish profitable businesses, and as a consequence coal mining was able to step up to another level. The wider application of the steam engine around 1700, together with the introduction of steel wire ropes, provided the ability to mine deeper to the more better quality coal seams, as well as winding larger loads of coal. Some of the early mines and businessmen operating them, include Jonathan Case and John Mackay.

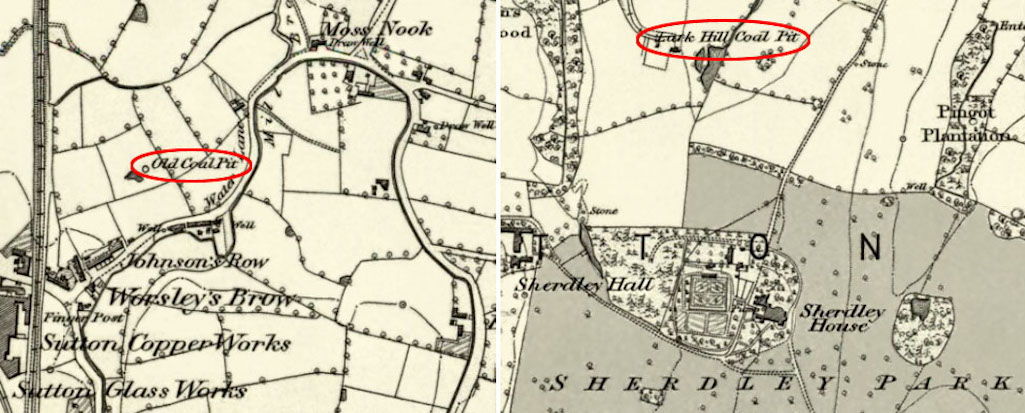

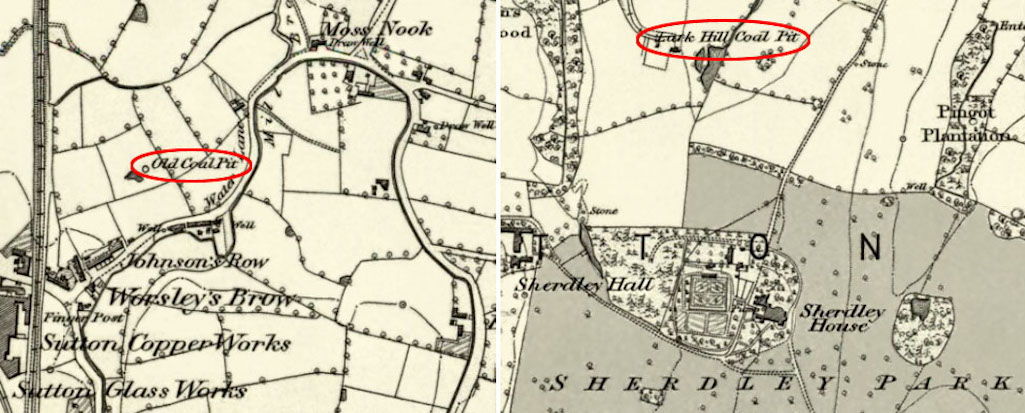

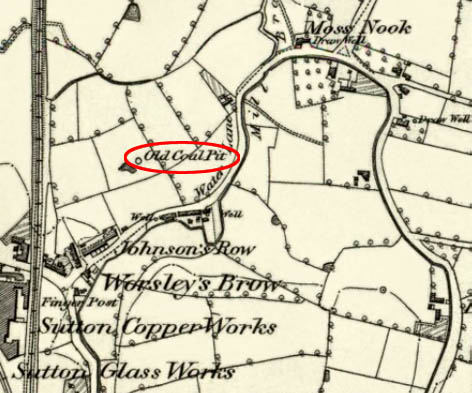

Left: Showing Bartons Bank Colliery as ‘Old Coal Pit’; Right: Lark Hill Pit near Sherdley Park - Both from 1846 OS map

Left: Bartons Bank as ‘Old Coal Pit’; Right: Lark Hill Pit - 1846 maps

Bartons Bank Colliery on 1846 map

On September 5th of 1839 the mine was put up for auction at the Raven Inn in St.Helens, where it was referred to as Lower Barton's Bank Colliery. However there is no known evidence of it being worked past that year, despite the pit's close proximity to the railway. This district, incidentally, later became known locally as the "Owd Bonk".

An interesting feature on the 1846 Ordnance Survey map is the notation to the Lark Hill Coal Pit. There are no records available that we can find to nominate who owned the pit, but it would have been situated on land owned by the Hughes family, with its coal lease royalty paid to them. The interesting point is that a rail line had been put in place from the St.Helens Runcorn Railway near Peasley Cross bridge, which together with the lease cost, suggests that it was capable of covering these costs. On the plan very little support buildings are indicated, so that it is felt ownership by the Bourne Robinson Company was a distinct possibility as it was close to Sherdley Colliery. The rail line connected to lines out of Peasley Cross Colliery, with both collieries being owned by this company.

In 1826 Ellen Hughes of Sherdley Hall gave a fifty year lease to Messrs. Bournes and Robinson for a mine in Sutton which led to an escalation in mining activity. This was largely through the creation of two new railways that could quickly connect collieries with their markets. Other pits were created at Sherdley (c.1873), Lea Green (c.1875), Bold (1876), Clockface (1890) and Sutton Manor (1901). The Sherdley estate profited by collecting rent from a number of mines, including the St.Helens Colliery Company, Sutton Heath and Lea Green Colliery Company and the Sutton Manor Colliery Company which continued well into the 1940s.

By the mid-1840s, the output of coal in St.Helens districts was a million tons a year. Consumption of coal had greatly increased due to a rapid expansion of factories, growth of the railways and an increase in the use of steam boats. However, being a miner was an especially hard life which was illustrated on December 13th 1843 at a public meeting of three hundred local colliers that took place at the Moor Flat in St.Helens. A number of Sutton miners attended and their working lives were summed up in a keynote speech delivered by William Dickson of Manchester as reported in the Liverpool Mercury of 15/12/1843:

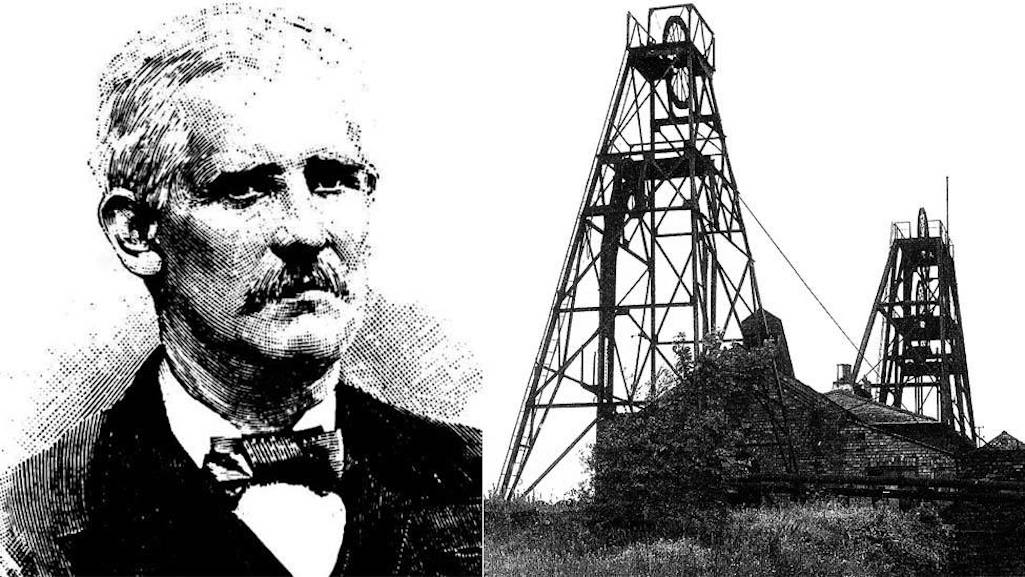

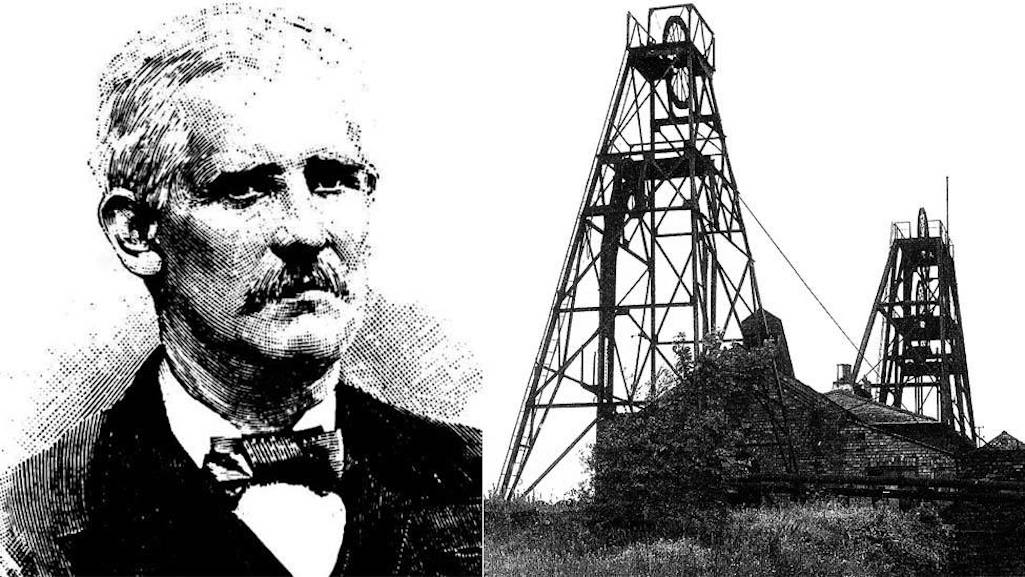

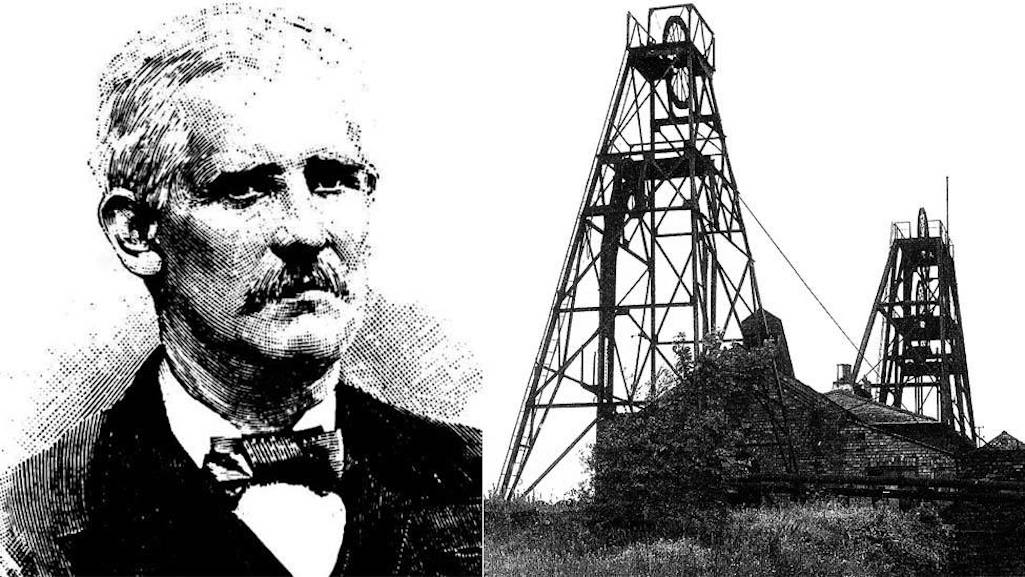

Left: Sutton-born Sam Woods; Right: Sherdley Colliery headgears which stood for many years after the pit ceased production

Left: Sutton-born Samuel Woods; Right: Sherdley Colliery headgears

Left: Sutton-born Sam Woods; Right: Headgears of Sherdley Colliery

In April 1893 the Lancashire Miners' Federation voted for a closed shop and the minority non-union workforce in Sutton and St.Helens' pits were given a deadline of June 24th to become unionised or face unemployment. The ultimatum was issued by miners' agent Thomas Glover (1852-1913), who called for the miners to 'prove yourselves men by joining at once'. In 1906 Glover became the Labour Party's first St.Helens MP. In June 1914 the South-West Lancashire Miners' Federation pursued what newspapers dubbed a 'crusade' against non-unionist workers. St.Helens was considered the 'black spot of Lancashire' for non-unionism, especially in Sutton, and strikes took place.

Alexandra Colliery named after the Princess of Wales who visited the Ravenhead Glassworks nearby in 1865

Alexandra Colliery named after the Princess of Wales who visited Ravenhead

Alexandra Colliery in Ravenhead

The near-national strike / lockout of 1893 badly affected many Lancashire pits and their communities. It was caused by a drop in the market price of coal and the colliery owners’ desire to compensate for reduced income by paying 25% less to their miners and drawers. There were many incidents in the Sutton district and on October 19th 1893, eighty police were showered with stones at Sutton Heath colliery by what the Manchester Courier said was a 'mob of 500 persons'. They'd assembled to try and stop some strike-breakers who'd been working in the pit and the men flung boxes of coal into the reservoir and threw stones down the pit shaft. After the police arrived in a number of wagonettes, the crowd was charged and they scattered in all directions.

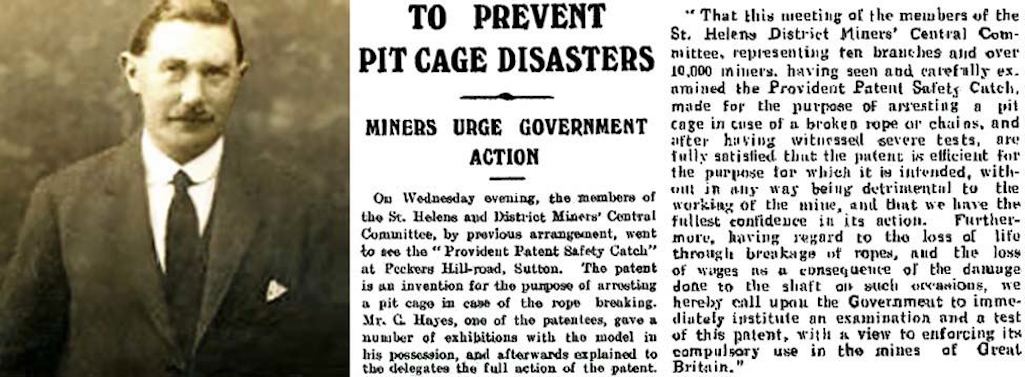

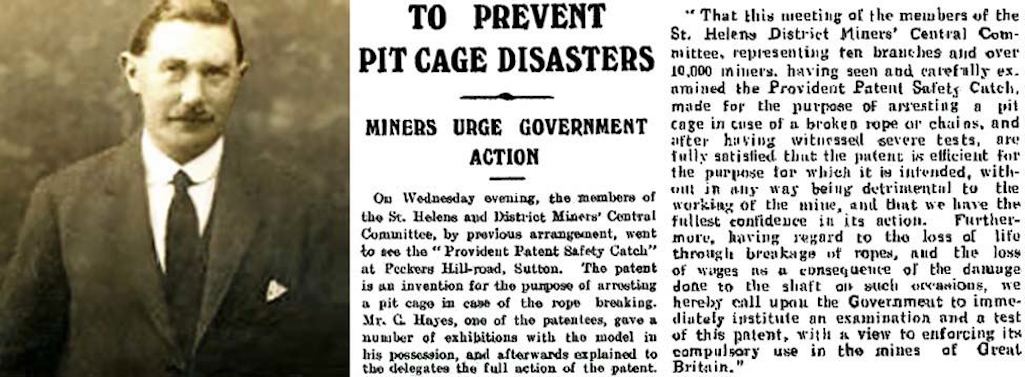

Inventor Charles Heyes and part of the St.Helens Newspaper account of July 2nd 1915 - Contributed by Mary Heyes

Inventor Charles Heyes and St.Helens Newspaper account of July 2nd 1915

Inventor Charles Heyes of Sutton

On June 30th 1915, Heyes demonstrated the invention at his Peckers Hill Road pub to members of the St.Helens and District Miners' Central Committee. The St.Helens Newspaper of July 2nd devoted many column inches to the demonstration, commenting how the attendees were full of praise for the safety device. However, Councillor Waring predicted difficulties in persuading the colliery owners to invest in it. So the committee called upon the government to immediately instigate tests of the Provident Patent Safety Catch and if they proved satisfactorily, make its use compulsorily in mines.

An improved version of the device was patented in 1921, however it's unlikely that it was ever used in mines despite the enthusiasm of its supporters. For one thing there were others offering similar safety devices. It is known that Heyes became a director of the British Quick Fire Light Company based in Hoghton Road. They seemed to manufacture brass fittings that allowed the transmission of gas to domestic fires, thus enabling a faster ignition of coal. However this would have had limited appeal due to the additional gas costs and Charles Heyes was made bankrupt in 1924. Shortly afterwards he left the 'Round House' - as the Locomotive Inn was known to Suttoners - and moved to Croydon to find work.

Winding house / pit headgear at Sutton Heath Colliery on the corner of Sutton Heath Road and Eltonhead Road

Winding house / pit headgear at Sutton Heath Colliery in St.Helens

Headgear at Sutton Heath Colliery

1926 march to Whiston demanding Poor Law Relief with Sutton Manor British Legion jazz band

March demanding Poor Law Relief with Sutton Manor British Legion jazz band

March demanding Poor Law Relief with Sutton Manor British Legion jazz band

Sutton Manor British Legion Jazz Band was formed during the 1926 lock out - contributed by George Houghton

Sutton Manor British Legion Jazz Band was formed during the 1926 lock out

Sutton Manor British Legion Jazz Band