An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 27 (of 95 parts) - Health & Sanitary Conditions in Sutton

d) Medical Practitioners in Sutton | e) St Helens Cottage Hospital and Sanatorium

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX Contact Me | Research Sources

c) Mental Health | d) Medical Practitioners in Sutton

e) St Helens Cottage Hospital and Sanatorium

Researched & Written by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

Old Sutton in St Helens

b) Industrial Health

c) Mental Health

d) Medical Practitioners

e) Hospital & Sanatorium

Fevers & Sewers in Sutton

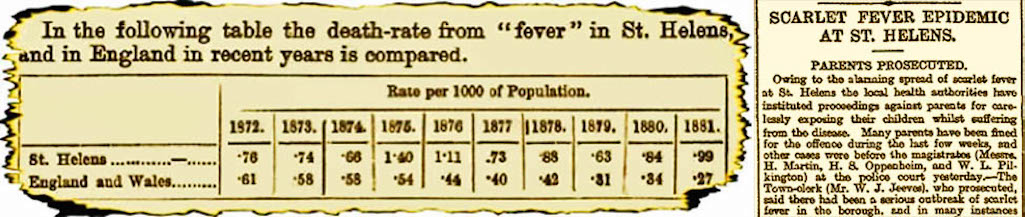

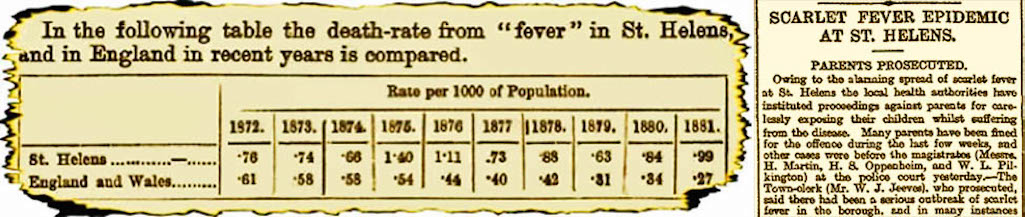

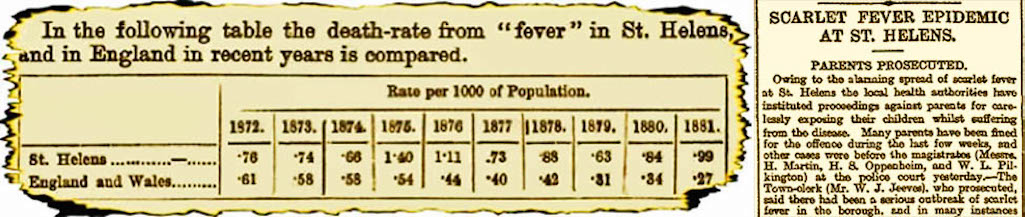

Throughout the 19th century as Sutton's industry expanded, there was a commensurate rise in Sutton's population. In June 1856, Rev. Henry Vallancey wrote how his congregation had 'increased largely' since 1849 when he first arrived in the township. Vallencey commented how 'the great mass of my people reside around the works' and he described how much building work was taking place, predicting a further rise in numbers in the immediate future. This was in spite of a high death rate in Sutton and in the other three townships of Parr, Eccleston and Windle that would comprise the future St.Helens borough. A combination of unhealthy work conditions, factory discharges into Sutton's 'Stinky' Brook, unsanitary living conditions and excessive drinking led to sickness and shortened lives.In 1885 John Spear was commissioned to report on the prevalence of 'zymotic' diseases such as typhoid fever in St.Helens and he commented that: '…the pollution of the atmosphere by chemical fumes and coal smoke is, as is well known considerable.' Spear's report revealed that the typhoid death rate between 1872-81 in the recently created St.Helens borough, was almost three times the national average. Sutton was especially afflicted by fever during this period. West Sutton had the highest rate of the six St.Helens wards and East Sutton fared only slightly better.

John Spear's report was scathing of the lack of a proper sewage system in St.Helens and he commented how waste discharges into the town's brooks from the various chemical, copper and glass works would often disguise the presence of raw sewage and the associated health risks:

Left: As Watery Lane wasn't connected to the sewers, the health hazards worsened when Sutton Brook flooded; Right: Spear's report

Left: Flooded Watery Lane; Right: Spear's 1885 report on zymotic diseases

Flooded Watery Lane and John Spear's 1885 report on zymotic diseases

St.Helens Corporation was slow to implement improvements. Dr. Robert McNicoll had become the town's first Medical Officer in 1873 and had pleaded in his annual reports for sanitary improvements. He was specially keen for a trunk sewer to replace the open brooks, which had been promised as far back as 1855. In 1888 at a St.Helens Town Council Paving, Highway and Sewering committee meeting Cllr. Greenough said “The sewers in Sutton are in a deplorable state, and it is time something was done.”

The main improvements only began in 1889, partly because the council had been embarrassed by six guests at a mayoral banquet contracting typhoid, of which two had died. Minds had also been concentrated by the sudden death of John Lowe, the Conservative Councillor for West Sutton, who had died of typhoid fever on December 6th 1888. Lowe had been conducting business in St. Helens on the previous Saturday but within four days had contracted the deadly disease and died. Lowe, of Elton Head Farm in Lea Green, was an ex-chairman of the Prescot Board of Guardians and had been first elected to St. Helens Council in November 1885. A quarrymaster by trade, Lowe had only been re-elected to represent West Sutton a few weeks before his demise.

On January 21st 1891 at a meeting of the Corporation's paving, highway and sewering committee it was agreed to spend £2121.10s for sewering and drainage of the Sutton district. Of this Rolling Mill Lane would cost £262 and Hill's Moss Road £156. However the scattered nature of Sutton's population meant that implementation had its limitations. In 1893 the St.Helens Improvement Act banned the building of back-to-back houses without backyards within the borough. This important legislation did, however, need much time to pass before it could have any significant effect on the town's citizens.

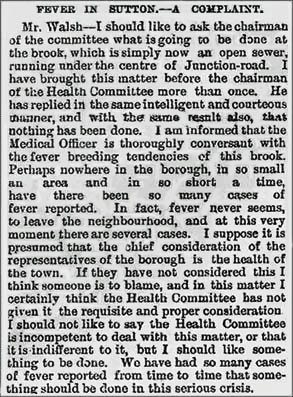

At a Council meeting in 1895, Councillor Charles Walsh - the representative for East Sutton who ran a draper's shop in Peckers Hill Road - took to task Councillor Forster, the chairman of the borough's Health Committee. Cllr. Walsh complained about the state of Sutton Brook around Junction Lane which he claimed was nothing short of an "open sewer". It was causing a "serious crisis" in the district with many reported cases of typhoid and other fevers:

Left: Spear's report on the continued prevalence of fever within St.Helens of 1885; Right: Liverpool Mercury November 17th 1896

Left: Spear's report 1885; Right: Liverpool Mercury November 17th 1896

Spear's report & Liverpool Mercury 1896

Scarlet fever, a highly contagious bacterial infection, was highly prevalent in Sutton around this time and a number of proceedings were brought against parents for exposing infected children. Elizabeth Rigby of 152 Robins Lane was fined five shillings on June 21st 1895, as was Ellen Lowrie on November 2nd 1896. Mrs. Lowrie of 137 Watery Lane had sent her nephew to school despite him 'peeling', the most infectious stage of scarlet fever. Emma Bath from New Street also received the five shillings fine. The Liverpool Mercury of 17th November 1896 said she had allowed her child to 'run about the streets while in a state of infection'.

From the middle of November 1895, St. Anne's schools were closed for six weeks to prevent the spread of scarlet fever. There was so much concern of disease that when Sutton Library opened in early 1897, a placard was put up banning book borrowers who lived in houses where there was scarlet fever. The bacteria in untreated milk was a prime means of transmitting it and other disease and so Cllr. Bates was keen for milk to be sterilised.

In April 1899 he visited Fecamp in Normandy as a member of a fact-finding delegation. They were informed how sterilising milk had significantly reduced infant mortality in the French town. Consequently St.Helens became the first borough in England to possess a municipal supply of sterilised milk, which was supplied to the populace at a specially low rate.

By 1906 there was concern that the health improvements seen in other parts of St.Helens were not being felt within East Sutton and Parr. A new sewerage scheme was seen as the answer and on October 19th 1906, a Local Government Board inspector held an inquiry at St.Helens Town Hall into the Corporation's plans to borrow £48,000 for this purpose. The sewer would begin at Marshalls Cross and traverse through Mill Lane and Parr to the sewage disposal works at Double Locks.

It was stated at the inquiry that the more densely populated parts of the district were already being drained into the Sutton Brook. Creating the new improved sanitation for the less populated parts of Sutton led to the death of Joseph Bray. The 63-years-old miner of 31 Frederick Street was buried alive by tons of clay that fell on him while excavating.

By the first world war there were still many privy middens in the Sutton district which were only emptied by the Corporation three times a year. The council were promoting a water carriage flushing system but it took decades before the middens were eradicated. In recent times, the notorious 'Stinky Brook', which factories have spewed waste into for many years, has improved. However, complaints are still made about the waterway that connects to the St.Helens Canal and Cllr. John Beirne made his opinions known in the St.Helens Star of April 6th 2006:

Day Sutton Brook Caught Fire (in Sutton Trivia page)

Download Spear's Report

Industrial Health and Injuries in Sutton

This website’s mineworking page demonstrates the hazards of employment in Sutton's pits and those who worked in the chemical and glass factories were similarly poor prospects for life insurance salesmen. They endured shortened lives through exposure to noxious fumes and by liver damage through drinking excessive amounts of beer. The chemical fumes rotted away all their teeth, and so they existed on 'pobs', a mixture of bread and milk plus copious quantities of beer. Many men drank because they could not eat and to cope with the horrendous conditions.An intake of 100 pints a week was not unknown, and employers weren't too concerned as long as workers could still do their job. Action would be taken, however, if employees became incapacitated. On December 11th 1876, James Barke, a watchman at Kurtz Chemicals, found Owen McKee of Sutton "very drunk and unable to perform his work", according to the Prescot Reporter's account (23/12/1876). On being spoken to by Barke, McKee became abusive and violent, threatening to "lance the watchman inside out". He was prosecuted and fined 5 shillings for being drunk and 10 shillings for assault and ordered to keep the peace.

Common health complaints included the miners' illnesses of pneumoconiosis, bronchitis and nystagmus. The latter was a condition caused by working in the dark in which the sufferer's eyes went round and round. Sutton glass workers endured heat stroke and 'glassmaker's cataract', which was caused by the glare of furnaces. Working very long hours was also not conducive to good health. The average working week in 1870 was 70 hours and children aged between 8 and 13 were allowed to work a 6½ hour day on condition that they received ten hours of schooling per week. Working conditions were poor and accidents were frequent and even by 1916, long shifts in factories were not uncommon. In August of 1916, sixteen-year-old Harold Taylor of Waterdale Crescent was killed at the Sutton Glassworks in Lancots Lane by a crane that toppled over. Forty-two-year-old crane driver William Chadwick admitted at the inquest to having worked a shift of over fifteen hours. When County Coroner Sam Brighouse quizzed him on this, he insisted that he wasn't fatigued and had previously worked much longer hours.

By the next day he had become quite ill and so visited Dr. Casey at his surgery on the corner of Junction Lane and Peckers Hill Road and he referred him to Providence Free Hospital. The Tolver Street medical infirmary, which had only been founded in September 1884 (initially as Hardshaw Hall hospital), didn't then have its own resident physician and he was initially seen by Dr. Fred Knowles of Hardshaw Street who was visiting his own patient there.

Dr. Knowles wrote to Crone and Taylor to enquire whether they would pay for his services but they refused. In their reply, the 'Bone Crushers and Manufacturers of Blood & Bone Manures' said that they were 'in no way responsible... we leave him in the hands of the hospital authorities'. Biddulph was dead within days from anthrax poisoning as a direct result of his work. The St.Helens Reporter of 22nd January, 1895 reported that the Coroner at his inquest had commented that the conduct of the firm had been 'quite extraordinary', although it was not uncommon.

Mental Health in Sutton

She had recently been a patient at Providence Hospital but had been so 'annoying' to other patients that she was discharged. Sutton GP Edward Casey certified Margaret as an imbecile and wanted her committed to Rainhill Asylum, although the magistrates were unimpressed. "Surely an asylum is no place for a child like this?", queried the chairman of the bench and eventually Margaret was sent to the workhouse. There seemed little evidence to justify her treatment, despite signs of 'mental derangement' when she was eight. Could she have been suffering from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder?

When it came to adults, alcohol was often blamed as the cause of their 'madness'. On September 9th 1891, Joseph Barton, who was said to have been 'respectably connected', went to Constable Hall to confess that he had committed a murder in Sutton and that men were pursuing him. A doctor certified him as being deranged through drink and magistrates ordered his temporary detention in the Whiston workhouse.

Then on November 15th 1900, the Liverpool Mercury reported that Ellen Sheridan of Herbert Street had spent a fortnight 'wandering about in terror', believing that people were going to murder her. Like Joseph Barton, Ellen was probably paranoid although paranoia was not Dr. Casey's diagnosis when he gave evidence to the St.Helens magistrates. Instead he said the cause was drink and the cure was 14 days in the workhouse. Alcohol was often the scapegoat for many forms of strange behaviour, which these days we are more likely to consider a symptom that might exacerbate a sufferer's condition, rather than cause it.

This was often the case with depressed individuals who committed suicide. 70-years-old butcher Thomas Johnson was clearly depressed when on April 13th 1871 he hung himself from a beam in his outhouse by Sutton Oak station. The Liverpool Mercury report said that he had been drinking heavily of late and had become temporarily insane as a result. This was a common inquest verdict, such as on February 20th, 1895 when farmer Thomas Ireland Lowe of Micklehead Farm, Lea Green, who'd previously worked Maypole Farm in Bold, poisoned himself with carbolic acid on the train to Manchester.

An interesting case of mental illness occurred on May 4th 1882 when William Foster of Peasley Cross Lane was apprehended by the police. The bottle hand at Cannington Shaw's had disturbed people by telling them that he had killed a man called Robinson in Yorkshire some nine years earlier. Foster was described in the newspapers as a man of 'peculiar temperament', who was sometimes very excited and danced and sang. At other times he was 'very melancholy' with fits of crying. These days I suspect that doctors would have little difficulty in diagnosing manic depression or bipolar disorder, as it's now known. The police released Foster without charge after making enquiries with colleagues in Yorkshire, although he had to endure the embarrassment of detailed articles in newspapers.

On July 2nd 1896, 44-years-old engine driver Robert Durning of Helsby Street committed suicide by cutting his throat with a knife. At his inquest it was revealed that he had had an attack of influenza three years earlier and hadn't been well since. Of late Durning had been 'low spirited' and unable to work. These days a diagnosis of M.E. and depression might be made, treatment could be available and a suicide avoided.

By the turn of the 20th century, St.Helens had a Police Court missionary who looked after the welfare of vulnerable people who found themselves in court. However some court sentences for the mentally ill were still rather harsh. On April 29th 1914, John Eden of 67 Hills Moss Road at St.Helens Junction appeared in court charged with theft. The 61-years-old had helped himself to 94 pounds of seed potatoes from Travers Farm in Bold run by Mr. Pemberton as well as two wooden sleepers and a rail. Eden's wife Jane said he'd been "strange" for some time, picking up useless things and stuffing his pockets with them and the miner had been unable to work. Despite being clearly disturbed, Eden was given two months' imprisonment, the bench stating that the prison doctor would attend to him during his detention.

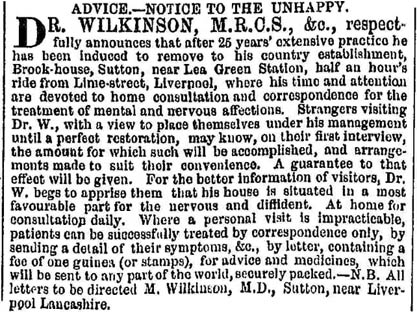

If you were working-class and depressed you were expected to 'pull yourself together'. However, if you had some money and were suffering from a 'nervous affection', you could avail yourself of specialists like Dr. Wilkinson who, for a while, was based at Brook House in Sutton. His advert in the Liverpool Mercury of August 7th 1855 invited 'unhappy' folk to visit him for a consultation. The 'nervous and diffident' could also send him a guinea (£1 5 pence) and would receive in return a letter and some medicine. A guinea was the equivalent of around £60 in today's money and well out of the reach of the poor, whereas the alternative 'pull yourself together' treatment cost nothing, apart perhaps from some lives.

Medical Practitioners in Sutton, St Helens

In fact John Spear reports 23,262 births and 12,170 deaths (including 3,501 children under 1 year) registered between 1872 and 1881. In the 1881 census the St.Helens population was 57,234 (11,000 in 1845 and 89,000 by 1900). Sutton's medical practitioners through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who did much to improve people's lives, were the aforementioned Dr. Edward Casey (practised in Sutton c.1882 - 1909), Dr. Thomas Pennington (? - 1891), Dr. Henry Baker-Bates (1891 - 1906), Dr. Frederick William Kerr Tough (c.1907 - c.1921 served in WW1 with rank of Major), Dr. Robert Cook (in 1911 census at 43/45 Peckershill Road - died suddenly on 7/1/1918 aged 41) and Dr. Fox.

Children had a saying about the various Sutton medics: "Dr. Casey set baits (Dr. Bates) to catch a fox (Dr. Fox). He is going to cook (Dr. Cook) him but will find it tough (Dr. Tough)." 94-year-old Catherine Williams vividly described in the St.Helens Star of October 6th 1983 how medical practitioner Dr. Casey, of 1 Junction Lane, would pull out aching teeth as well as treat patients' other ills. He'd charge sixpence for each painful extraction, although if a child didn't cry or shout, the Irish doctor would return their tanner! Catherine wrote that he was a character of "unusual rarity" who was a "Godsend to the many-starved children of those days".

Edward Casey was born just outside Dungannon in Co. Tyrone, Ireland c.1850 and qualified in Aberdeen in 1881, arriving soon afterwards in Sutton. He is said to have invented a treatment for indigestion and owned much local property. Casey had houses and shops in Edgeworth Street, Peckershill Road and Fisher Street and left an estate valued at £24,470. Of this £100 was bequeathed to the Rector of St. Anne's monastery.

From 1913 to March 1916, Dr. Bird cared for Sutton folk as assistant to Dr. Tom O'Keefe of New Street before dying from pneumonia at the young age of 33. Dr. J. O'Mahony was another assistant to Dr O'Keefe who in April 1920 spent a few weeks in the Borough Sanatorium suffering from scarlet fever. There was also Dr. Donald Edward Henry Campbell who lived and had his surgery at Phoenix House in Peckers Hill Road for many years from c.1920. In June 1921 Dr. Campbell was divorced by his wife after being accused of sleeping with her friend and making her pregnant while the couple were living in Hove.

Other more recent medics (1940s - '70s) include Dr. Sullivan who became Bold Colliery's doctor, Dr. Lennon, Dr. Thomas Sutton and Dr. John Unsworth - who was followed by Dr. Rory O'Donnell - whose surgery was in Leach Lane.

Mention must also be made of Nurse Barbara Lacey (Brown) who was born and bred in Sutton at 8 Ditch Hillock. On April 1st 1917 Queen Alexandra, the widow of King Edward VII, appointed Barbara as a Queen’s Nurse. This meant she was a district nurse and member of what is now the Queen's Nursing Institute. Barbara was a familiar figure for some twenty years, pedalling in her nurse's uniform round the district from her home in Irwin Road. All that cycling was clearly good for her as Barbara was ninety-six years of age when she died in 1985. Then there was Nurse Smith, a midwife who brought many Sutton babies into the world and who married a coal dealer in Peckershill Road. Her father survived the Titanic disaster, only to drown in 1915 when his ship was sunk by a German U-boat.

If you couldn't be saved by Sutton's doctors, you were likely to meet undertaker and blacksmith Isaac Ashton of Fisher Street

If you couldn't be saved by Sutton's doctors, you were likely to meet undertaker and blacksmith Isaac (Ike) Ashton of 21 Fisher Street

If Sutton's doctors couldn’t save you, you might meet undertaker Ike Ashton

St Helens Cottage Hospital & Borough Sanatorium

The work of health practitioners, plus pressure from trade unions, concerned citizens and politicians led to improved living conditions and sanitary disposal and a gradual improvement in the populace's health. The creation of what we now call St Helens Hospital in Marshalls Cross Road in Peasley Cross, then part of Sutton, also played a crucial role in improving health.

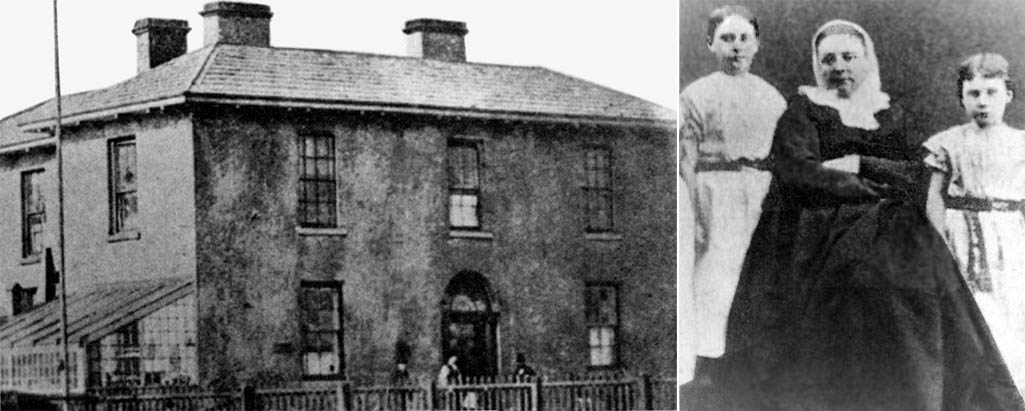

Left: The cottage before it was converted into a hospital; Right: Matron Martha Walker with two workhouse girls

Left: Cottage before it was converted into a hospital; Right: Martha Walker

The cottage before it became a hospital and Matron Martha Walker

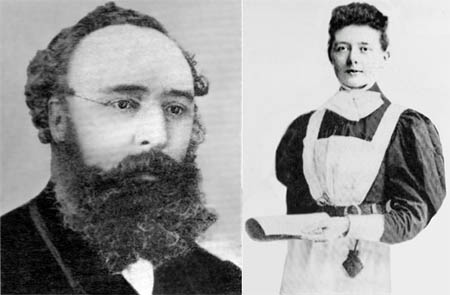

The conversation turned to the lack of an infirmary in St Helens and Kurtz told Allen that if he would find a suitable site, the chemical boss would find the money. So Allen quickly found a house in Peasley Cross for the new hospital, which had been the home of Sir David Gamble’s father. It was in a very dilapidated condition and required large-scale renovation to make it fit for purpose, which cost Hughes £462. There were only three furnished rooms which accommodated nine beds in total.

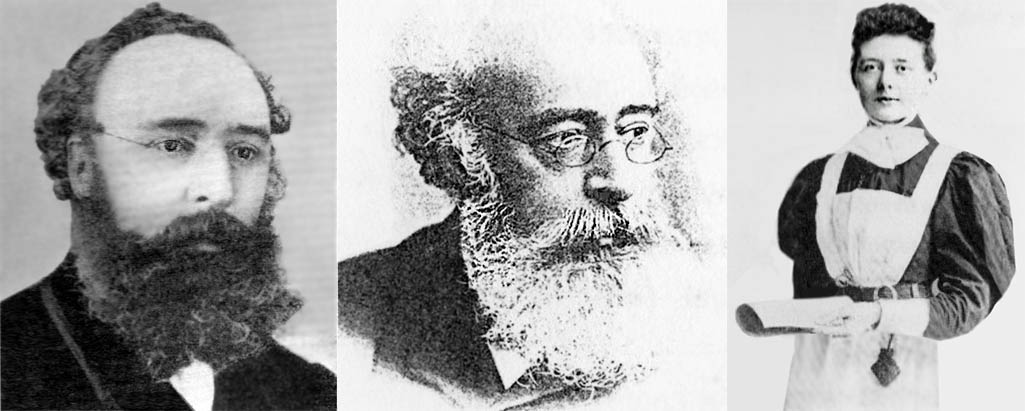

Two photographs of chemical manufacturer and benefactor Andrew George Kurtz (1824 - 1890) and Matron Harriet Oates

Two photos of Andrew Kurtz (1824 - 1890) and Matron Harriet Oates

Andrew Kurtz and Matron Harriet Oates

James Davies of St Helens Collieries is credited with organising the penny-a-week subscription system, with Martha Walker having thought it up. She was the Quaker lady who had served in a hospital camp during the American Civil War and was the new infirmary’s first Matron. Martha was assisted in her work by three young orphans from Whiston workhouse. One girl was only seven and the other two were just eight years of age.

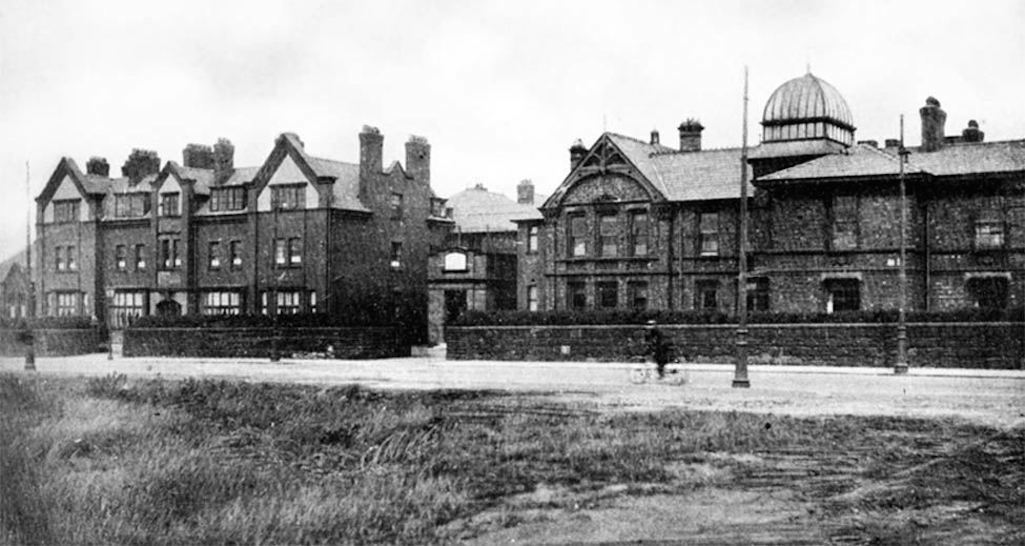

The St.Helens Cottage Hospital in Marshalls Cross Road in Peasley Cross

St.Helens Cottage Hospital in Marshalls Cross Road in Peasley Cross

The St.Helens Cottage Hospital

There were several Matrons who succeeded Mrs. Walker who didn’t last very long until in April 1888 Annie Stocks took charge of the hospital. The 33-year-old lasted seven years, the longest term for a Matron so far. However her longevity was considerably exceeded by Harriet Ross Oates, who was in charge for 32 years from 1895.

By 1896 there was a total of 50 beds and the extensive improvements and extensions belied the cottage hospital description. So in that year it changed its name to St Helens Hospital. In 1898 Ann Garton's bequest of £28,675 provided the hospital with some much-needed financial security. Miss Garton had ambiguously stated ‘St Helens Infirmary’ in her will, which led to a dispute with Providence Hospital that had to be settled in court. A women’s ward at St Helens Hospital was named after Ann Garton in appreciation of her generosity.

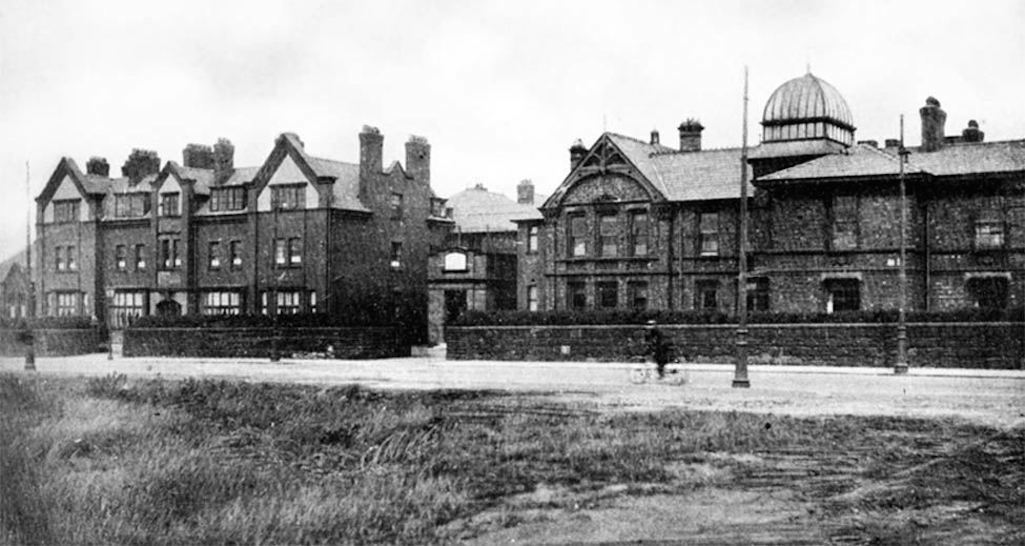

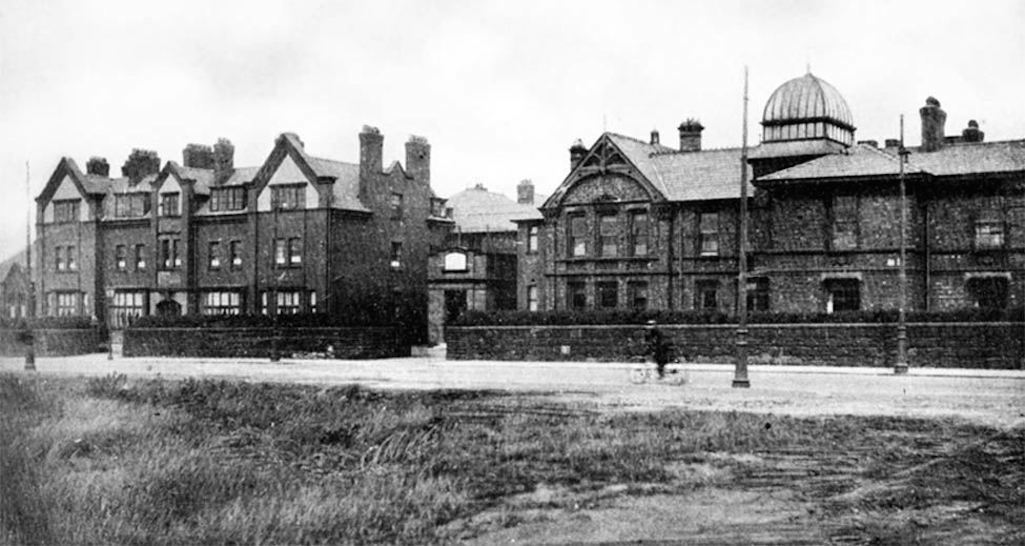

Another view of St Helens Hospital (formerly Cottage Hospital) in Peasley Cross

Another view of St Helens Hospital (formerly the Cottage Hospital)

Another view of St.Helens Hospital

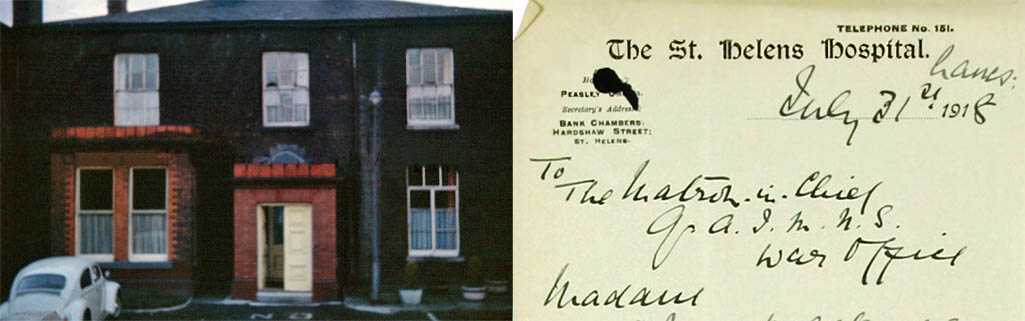

The Great War was a challenging time for the hospital as large numbers of wounded and sick soldiers were treated there. During the year ending April 1917, there were 1585 patients of which 477 were soldiers. The hospital's income was also reduced with many of their subscribers in France. For the year ending April 1916, there was a decrease of £931 in the penny-a-week subscriptions.

They also lost their Matron Harriet Oates for a time. She was enrolled in the Territorial Army Nursing Service Reserve from 1909 to 1927 and from August 1914 to May 1917 served as Matron of a military hospital at Fazakerley. In 1916 Harriet was decorated by King George V at Buckingham Palace with the award of the Royal Red Cross, which allowed her to bear the initials RRC after her name.

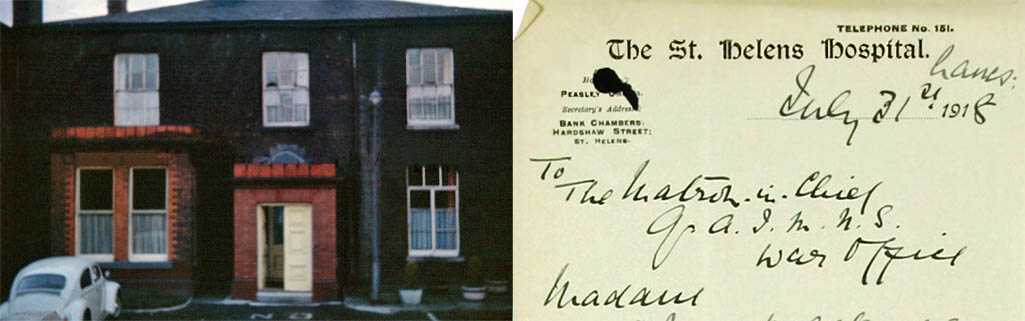

Left: The oldest part of St Helens Hospital pictured in the 1950s; Right: Letter with hospital letterhead written by Matron Oates

Oldest part of the hospital in the 1950s and letter written by Matron Oates

Oldest part of the hospital in 1950s

The St Helens Reporter of February 13th 1920 carried an appeal from St Helens Hospital for more funds. The war-time inflation had led to a considerable deficit in their accounts and the hospital was now asking their subscribers to pay twopence instead of a penny. During 1922, the hospital treated 860 men, 344 women and 315 children. Colliery workers and their dependants comprised the lion's share with 853 admissions.

Two views of the nurses’ home opened in the grounds of St Helens Hospital in 1939 accommodating 76 nurses and sisters

The nurses’ home was opened in the grounds of St.Helens Hospital in 1939

The nurses’ home was opened in 1939

The penny-a-week scheme became penny in the pound in 1929, as contributions became linked to earnings. So if an employee earned £2 per week, they paid twopence and threepence per week if they earned £3. In June 1939 a new nurses’ home was opened in the grounds of St Helens Hospital at a cost of £32,000, which accommodated 76 nurses and sisters.

Carol singing at St Helens Hospital pictured at Christmas during the 1950s

Carol singing at St.Helens Hospital during the 1950s

Carol singing during the 1950s

This was also known at various times as the Borough Sanatorium, Fever Hospital or Isolation Hospital. The latter was an appropriate name as there was little treatment available for many conditions in the hospital's early days. So isolating an infected person from society to prevent contagion was its main raison d’être. In fact a Mrs. Pearce and her daughter, with no medical training, were charged initially with looking after the patients.

At St Helens Corporation's monthly council meeting held on December 1st 1886, a long discussion took place at to whether a trained nurse should be employed instead. It went to a vote and health chief Dr. Gaskell won the argument for a medical presence at the Infectious Diseases infirmary. The council meeting also considered an application from the St. Helens Tramway Company to use steam traction trams instead of horses. Progress was coming to St Helens!

St.Helens Borough Sanatorium, also known as the Fever or the Infectious Diseases hospital

St.Helens Borough Sanatorium was also known as the Fever hospital

The St.Helens Borough Sanatorium

As revealed in the 'Fevers and Sewers in Sutton' article at the top of this page, scarlet fever was highly prevalent in Sutton during the 1890s. Councillor Charles Walsh, representative for East Sutton, reported to a St Helens Town Council meeting on September 7th 1892 that there was an "epidemic of fever" in the Sutton district adding that:

A notice that was placed in the St.Helens Lantern newspaper of October 18th 1889

A notice that was placed in the St.Helens Lantern newspaper in October 1889

St.Helens Lantern October 18th 1889

The census conducted on March 31st 1901 provides a snapshot of the types of patients at both infirmaries. Of the 29 male patients over 12 years of age in the main hospital, twelve were mineworkers (11 hewers), five glassworkers and three chemical workers, underlining the dangers of such employment. The remaining nine male patients included six children just seven years or younger.

The matron then was Harriet Oates, who had seven nurses under her, along with six ward, laundry, house and kitchen maids, plus a cook and porter. There were 14 female patients, of which half were under 16. The fever hospital, as the sanatorium was often described, was little more than a children's hospital in 1901. Of its 58 male and female patients, astonishingly only three were over 14. In 1911 the matron was Miss Burgess and its administration block was Peasley Vale House, the former home of Richard Fildes of St Helens Gas Light Company, John Fenwick Allen and coal boss Benjamin Biram. For more than twenty years from 1917, Edith Carder served as matron of both the Peasley Cross and Eccleston Hall sanatoriums, as well as the Cowley Hill Maternity Hospital.

On Christmas Day 1916 there were 115 children and 2 adult patients in the Borough Sanatorium, with recent epidemics having inflated patient numbers. The St Helens Reporter said it had been an ‘exceedingly pleasant day’, adding that:

The unveiling of the spectacular new £100 million hospital in 2008 with its purple, yellow, red, orange and green zones ended an important link with the past. I wonder how many readers of this page have been grateful for the care that they have received from the doctors and nurses in the old Gamble, Garton, Hammill, Pilkington, Kurtz, Rennie and Bishop wards and clinics? These were named after benefactors, management committee chairmen and medical practitioners at the Hospital who helped to improve and save lives in St Helens. Their eponymous wards have now gone but hopefully their contributions will long be remembered.

Ferrie Ward (opened 1992) – The Outpatients Department was named after G.P. Dr Archibald Ferrie

FR Dixon-Nuttall X-Ray Room (opened 1929) – Named after the bottle manufacturer after leaving £2,500 in his will to the hospital

Gamble Ward (opened 1903) – Gamble family i.e. Sir David Gamble Trustee and Josiah Gamble

Garton Ward – After Ann Garton who bequeathed £28,675 to the hospital

Hammill Ward – In honour of hospital secretary John Hammill chartered accountant and brother Martin Hammill, a chemical manufacturer

Hazels (or Hazel) Ward (opened March 1935) – Children’s ward named after The Hazels, which was the Pilkingtons’ home in Prescot

Kurtz Ward – Chemical manufacturer Andrew George Kurtz

Pilkington Ward (opened 1903) – Trustees William Windle Pilkington, Richard Pilkington and Arthur Pilkington

Rennie Ward (opened Feb. 1953) – ENT / ophthalmology ward named after Alderman Robert Rennie, who chaired the hospital management committee and had been Mayor