An Illustrated History of Old Sutton in St Helens, Lancashire

Part 62 (of 95 parts) - Memories of Sutton Part 12

Compiled by Stephen Wainwright ©MMXX

'Memories of Sutton Manor' by Stan Johnson

I have some good and some bad memories of the days when I worked down No. 1 shaft at Sutton Manor. I was there from 1955 to 1962 and chose mining in my last term at Dovecot Secondary School in Page Moss, near Huyton. The headmaster, Mr. Atherley, summoned all the school leavers to the main hall and asked each individual what type of employment they had in mind. There were many different answers and mine was based upon what one of my best friends, who was working at Cronton Colliery, had told me. So I said to the headmaster that "I'd like to go into the mining industry."

I will always remember my first underground visit, which was to Lea Green Colliery. I think that the winder guy knew that trainees were having a visit and for fun (his fun not ours!), he lowered the cage at his normal speed and frightened the lives out of us. Three bells and down we went. Most of us left our hearts at the pit head and I will never forget that feeling when the cage that was coming up, passed us on the way down. Our ears popped and we were deaf for about five minutes. Lea Green was well known by most of the trainees because of its terrible smell. It was very gassy and you could smell it in the air and even when on the miners' bus, we knew when we were getting close to Lea Green by the smell.

One guy in our group was sacked immediately for throwing a rock while we were on an underground visit. We soon realised that the two things that were very important to a miner were your ears and your nose. Your ears to listen out for the moaning of the timber pit props that supported millions of tons of rock above. And your nose to smell the gases that were below ground, firedamp being the most deadly.

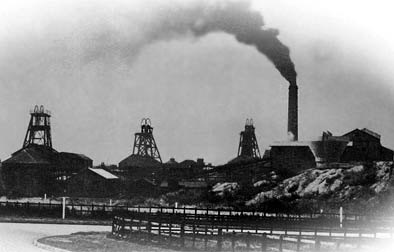

Sutton Manor's No1 Pit shaft is on the right - taken in the yard towards houses in Tennyson Street and Milton Street

Sutton Manor's no1 shaft is on the right - taken in the yard towards Tennyson Street & Milton Street

Sutton Manor's no.1 shaft is on the right

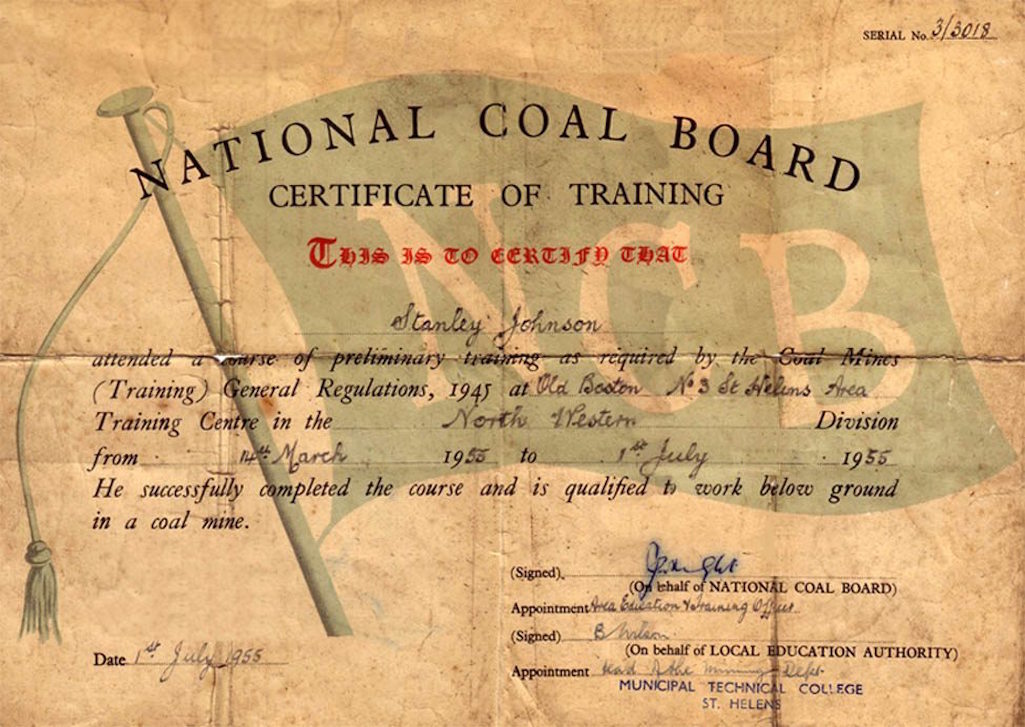

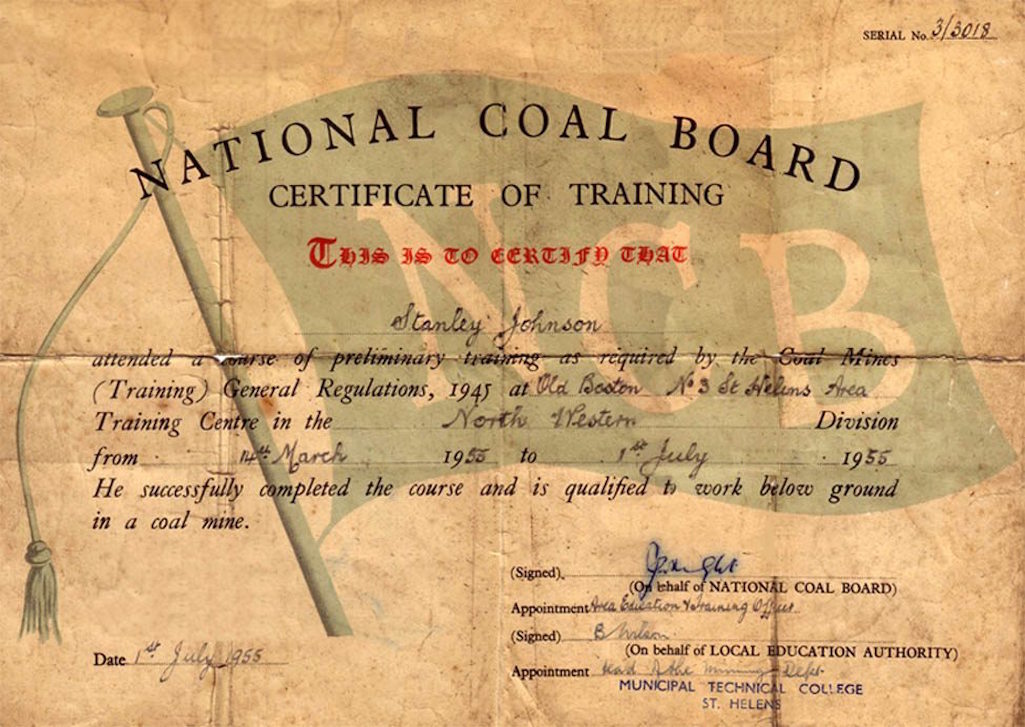

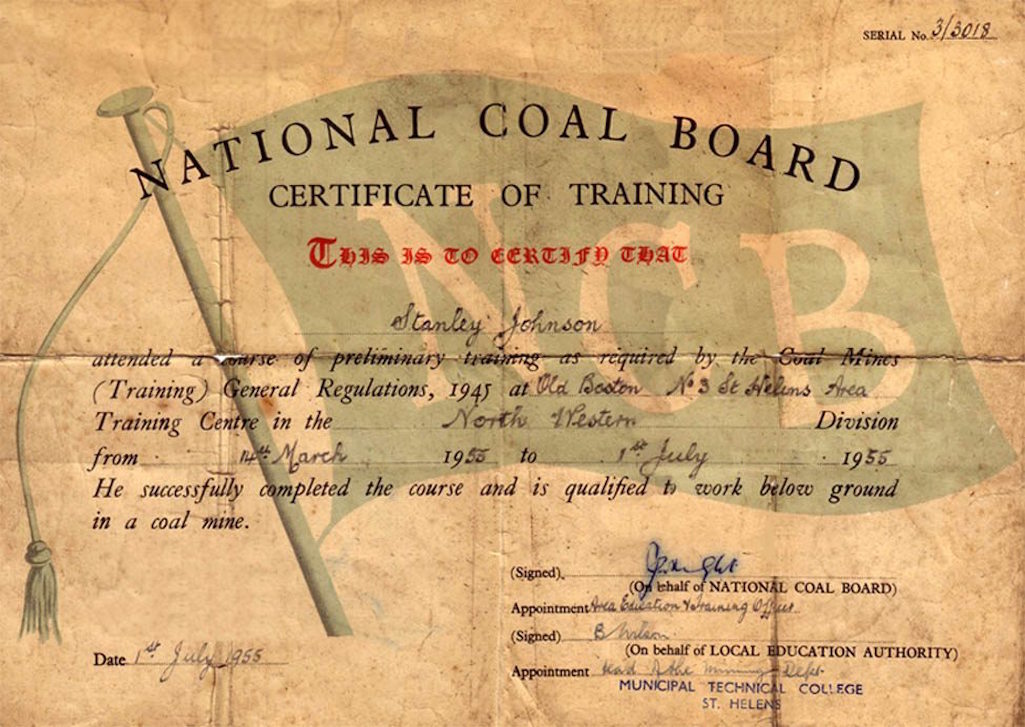

Stanley Johnson's National Coal Board training certificate from 1955 - contributed by Stan Johnson

Stanley Johnson's National Coal Board training certificate from 1955

Stan Johnson's NCB training certificate

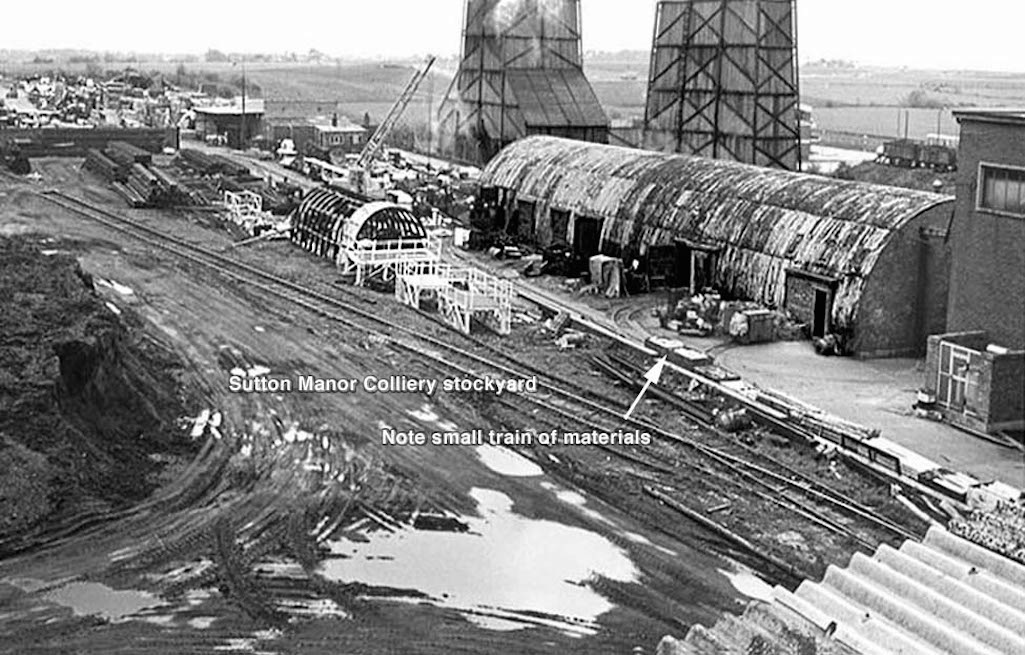

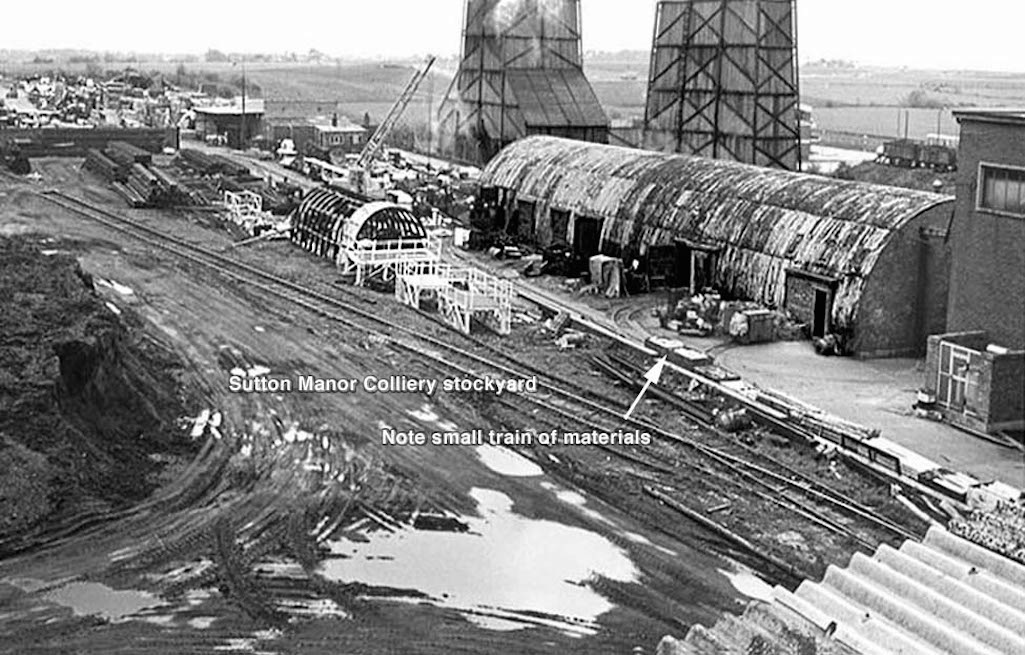

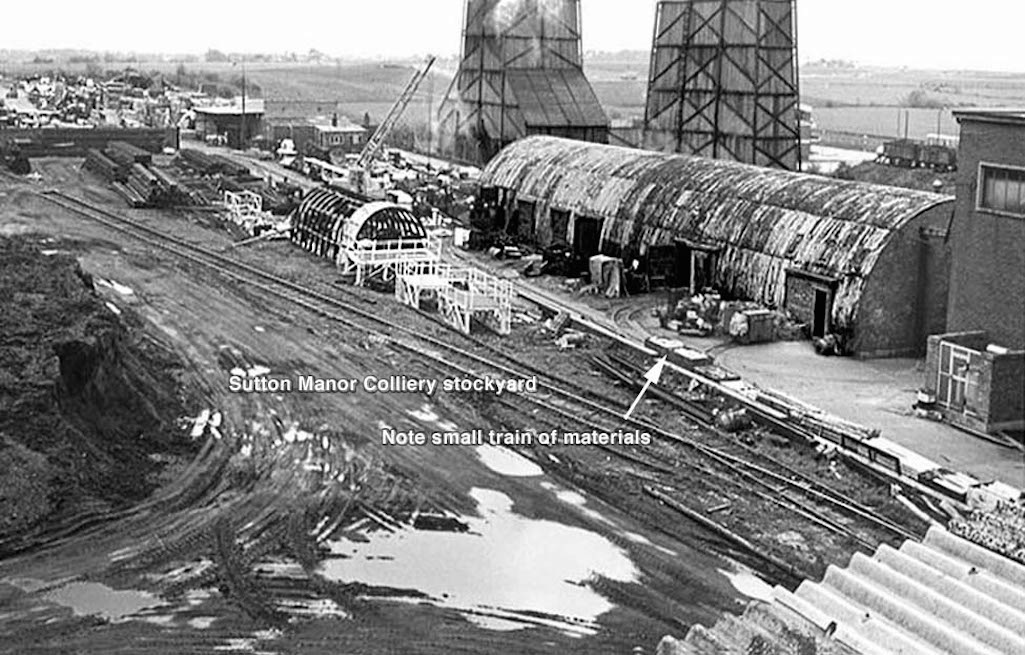

Sutton Manor Colliery stockyard with loading crane - note the small train of materials ready to go underground which ends with two tubs that might be full of bags of 'Stone Dust'. Before these are the longer carriers containing wooden props, that were often called trams and which were two tubs long, and these would all travel right to the shaft - contributed by Ray Darwin (caption by Harry Hickson)

The Sutton Manor Colliery stockyard with loading crane

Colliery stockyard with loading crane

Then we went to the Lamp Room and we were given a helmet lamp and a black battery that we wore on our belts. The battery was about 2 inches thick, 8 inches high and roughly 5 inches wide and was quite heavy for its size.The helmets that we were issued were white and to avoid being known as “new guys” because of the white helmet, we tried to scratch and darken them, so we wouldn't be made fun of. I scratched off the leather that covered the steel toe capped boots and polished the steel to make them shine.

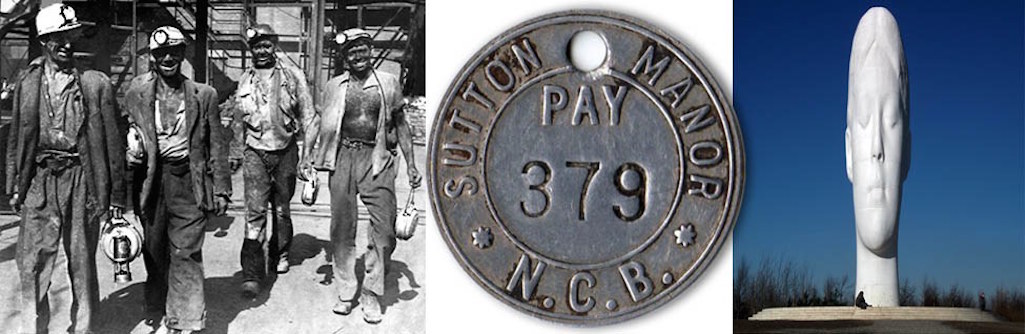

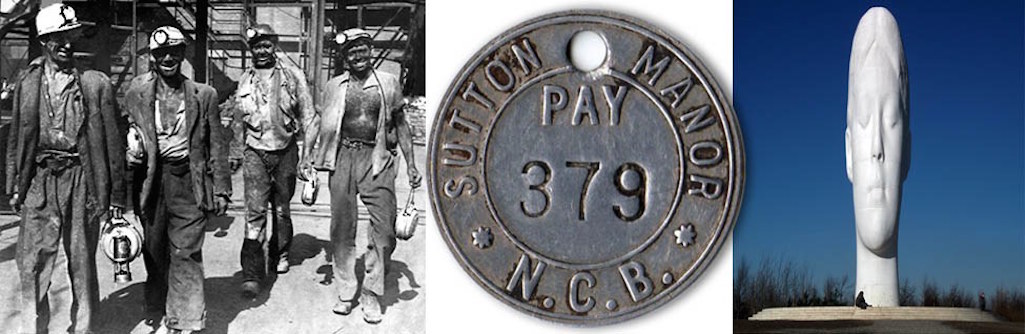

Then we were shown the procedure at the Pit Head and how to get in and out of the cage. Then we were given a Tally (with a number on it) and told that it was “extremely important” (They certainly drilled that into us). Before we went down, we were told that we “must” put the Tally on a hook which was on a big board and when we surfaced we “must” take it off. This procedure would allow the men in charge to know who was still down below and who had surfaced. This, (to me) was a simple but very effective safety measure and proved itself many times over the coming years.

If any man was NOT detailed to be below ground and whose Tally was still on the board, he was declared missing and there would be an immediate inquiry or search to find out why his Tally was still there. Simple but brilliant! I've not seen the Dream sculpture at Sutton Manor yet, but I understand the plinth that it sits on represents a miner's tally.

a) Manor miners with typical clothing including helmets complete with lamp & cable that goes to the battery on their hip - note metal water bottles - contributed by Ray Darwin; b) Colliery Tally; c) Dream sits on a plinth in the shape of a tally

a) Manor miners; b) Colliery tally; c) Dream on a plinth in the shape of a tally

Left: Tally; Right: Dream’s plinth

I was born and bred in the Huyton suburbs of Liverpool and although St.Helens is not very far from the city, the locals spoke in a totally different way. For instance they called mice (there was loads of them down below) “moggies”! In Liverpool a moggy is a cat. We had heard in school that there were mice and rats in mines but it was a big shock when one of the locals said: “There’s a moggy”, as we looked round for a cat!

I was quite surprised when I first went down below as I was expecting little dark tunnels. However, at the bottom of the shaft, the tunnel was massive and there were electric lights. It was as clear as day with lots of men and hundreds of tubs all in a line, full of coal and with different colours splashed on them, waiting to be taken up to the surface. As one cage went up, the other came down with supplies. They used to splash a type of whitewash on the coal in the tubs, so they knew which face it had come from. There were different colours for different coal faces and the Deep coal was coloured blue.

Sutton Manor Colliery was generally well lit as displayed in this photograph. This is the 'loading side' at the pit bottom as shown by the running in slope of the track and the stops which hold the tubs back until loading.The cage is shown empty on the right and is ready to take men up. This photo was probably taken during a holiday period because of the lack of tubs and people. In a production period, full tubs would be banked right back from the cage - contributed by Ray Darwin (caption by Harry Hickson)

Inside Sutton Manor Colliery which was generally well lit, as shown in this photograph

Inside Sutton Manor Colliery

I had also imagined that it would be very dusty and hot underground but there was always a lovely slight breeze of air along the tunnels. That is until somebody threw the “stone dust” into the air as the breeze would carry it away and if you were working 'down breeze' you’d get covered in the stuff. Stone dust bags were about the same size as a bag of cement, and were positioned every so often along the tunnels. This was a safety check feature for the Government Mine Inspectors who made frequent inspections of mines and checked the results of its application. It was a very fine ground stone (limestone was one type), with one essential requirement that it must not coagulate in the varying moisture levels commonly found in mines. It worked by covering the ever present coal dust, and hence would reduce the temperature to it following a gas explosion.

No. 1 shaft had a pump room level half way down and every so often on the way up without any warning, the cage would suddenly slow down and stop. The guys would all gasp and if you didn’t know why this happened, you were terrified. The reason was that in the cage coming down was a pump engineer and the two cages had to stop to let him get out. After knowing why the cage had suddenly stopped, we'd have a laugh about it. But believe me, the first time it happened, I thought that the winding rope had snapped.

One day in 1958, the winding rope did snap and the cage was crushed to about 2 feet high. I was in the last cage down at three minutes to seven, about 3 or 4 minutes before it snapped and I heard the terrible noise coming from the shaft. Then the almighty crash as it hit the level that I was working at. They were at that time drilling deeper for more coal seems and had thick beams at the current working level, but the cage went right through them. It was a two-tier cage about 10 or 12 feet high and I can remember about three weeks later seeing it in the colliery yard. During training we had been told how to position ourselves in the cage when being lowered or raised. We were instructed to “sit on our haunches” and crouch down. Well, after seeing that cage and the state it was in, I don’t think it would have mattered how we were!

Do you know how ‘Scotch’ was used in mines? They were part of the slowing down or stopping of coal tubs. Haulage workers jammed lengths of steel rods into the rear wheel spokes of tubs when uncoupling them from the endless ropes after being brought up brows or slopes. They came up in threes and were attached by a length of chain at the front and also at the back. The tubs had three small links of chain attached to the back and on the front of the tub was a hook. It was a BIG no no to put any part of your body in between the tubs when coupling them together. Instead they had to couple them from underneath. Many accidents were caused by lads who didn’t apply this very important rule and I have on many occasions seen men or boys being crushed or having their arms, fingers or hands badly damaged.

Although the solid, heavy tubs down Sutton Manor are empty here and not in a haulage situation, you can picture how three being connected together while in motion by a chain and hook that connected the end tub to a haulage rope, was a dangerous operation. In the 19th century, many boys lost their lives by getting trapped between tubs - contributed by Ray Darwin (caption Harry Hickson)

Heavy tubs inside Sutton Manor colliery, which could be very dangerous

Heavy tubs inside Sutton Manor colliery

Each colliery had its ghost and down No.1 we called our’s "Stuggy". Apparently he was a collier who was killed in the early days of Sutton Manor and many miners did believe he existed and there were stories going round about sightings of him. One thing I can say is that when you are all alone in a silent, dark low tunnel with only your helmet light to see with, you do imagine things and it’s quite scary. I was once doing some paving in an unlit tunnel, on my own, near a set of “air doors”. There were quite a few sets of “air doors” situated within the mine workings and you had to close one door before opening the other. In fact it was almost impossible to open one, while the other was still open. It was all down to air flow throughout the mine. Some of them were badly made and in some cases wouldn’t close properly. You had to give them a good push to ensure that they were closed, otherwise it was difficult to open the other door.

Another thing that was hard to get used to was when they fired explosives on a working face. There was a dull "thud" and the flow of air would change and play tricks with your ears. After months doing the haulage work, I got a job which I liked very much as a salvage engineer. I was a safety conscious type of guy and maybe somebody higher up noticed. To me it was exciting but dangerous and I used to retrieve props, rings and machinery from old workings. Most of the roof falls which happened I caused myself, but from a safe distance away! I was glued to the screen during the Chilean mine rescue. What a wonderful feeling to have watched that. It was disasters that made me want to join the Mines Rescue Service and I myself have crawled through roof falls only 18 inches high.

In the time that I was working at Sutton Manor, they were gradually introducing the steel hydraulic pit props. I can say without any hesitation that nobody liked them. They would bend under weight without any noise and if not put in exactly vertically, would sometimes shoot out under the weight. The miners' friend was the old wooden pit props. You could hear them moaning and cracking. They (unlike the steelies) would at least give you a warning, so you had time to get away knowing something was about to happen. That was part of my day's work, going to an exhausted coal face with another guy to retrieve the old, but still good, pit props and any unused machinery. Most of the smaller tunnels (especially close to and on the old coal face) had the wooden or hydraulic props in them. My job was to get them out, load them on tubs or trams. A tram was a little longer than a tub with a small post in each corner and was specially made for transporting rings, large timbers and other large items.

The colliery lamp room's Davy lamp section with Tommy Stanley taking pride in maintaining their highest efficiency

The colliery lamp room's Davy lamp section with Tommy Stanley in charge

Lamp Room at Sutton Manor Colliery

One day after causing a few roof falls and getting out what we could and moving to a safer place, we stopped for our lunch break and rest. I thought my pal was having a nap, but it wasn’t until I saw the flame on my Davy Lamp, that I realised that we were sitting down where gas was present and my pal wasn’t having a nap, but drifting off under the gas. I immediately dragged him away to where there was more of a breeze and he came to. Wasn’t that lucky? Some people are more likely to go under faster than others. I must have been the latter. At the time we just thought nothing of it, but looking back at the situation, WOW!!, weren’t we lucky? I could have gone under too and I wouldn’t be writing this now.

This scene could easily be Stan making an assessment prior to removing all the shown equipment. Note the supported area of timber props and steel roof girders which are potentially unsafe. The wedges that are used to make the props tight appear to be almost out or on unsafe angles and there is 'extra' ventilation trunking behind the props. Also note the white residue on the middle props, pipe, and floor which is the aforementioned Stone Dust. The underground worker appears to be checking the situation, and with the Davy lamp, he may be about to undertake a test for gas in the roof area - contributed by Ray Darwin (caption by Harry Hickson)

An underground scene down Sutton Manor Colliery in St.Helens

Sutton Manor Colliery underground

One of my not so happy memories of those days was that the last winding of men was at 07-00hrs, and if you missed the last wind, you had to miss a day’s work. Then at around 2-30pm, you would finish off whatever you were doing and make your way to the pit bottom, ready to be brought up. But nine times out of ten, there was a big queue and by the time you got to the surface there wasn’t time to have a shower and get changed or you would miss the miners’ bus W3 or W5. So sometimes you would go home dirty or you’d have your shower and miss the bus, then have to get a public transport bus home a few hours later. Mum and Dad would go mad if I hadn't showered. The little cottage that we lived in was over 200 years old and the hot water was heated by a back boiler stored in a tank and which only put 4 or 5 inches of hot water into the bath. Then it ran cold and it would take hours for the fire to get it hot again.

Sometime in late 1959, one of my pals Gordon (I can’t remember his last name) lost his right arm. This was after doing something that we were told not to do, which was ride on the conveyer belts. A lot of the guys used to do it, until they began taking the men to the pit bottom by a locomotive train with small coaches. But Gordon got his trousers stuck fast in the staples that held the belts together and was dragged over the end pulley. His arm was hanging off, but he managed to walk some distance before collapsing and was brought up by a medical team.

About 5 or 6 months later, I had just got out of the cage and had picked up my tally and was going down the steel steps to the colliery yard, when I noticed a crowd just by the Lamp Room. When I got closer I could see that it was Gordon, so I got through the crowd and came face to face with my friend. I was wondering how to greet him, knowing what had happened. His right arm lifted up to shake my hand, but I didn’t shake it, I gave him a big hug instead! I lost contact with Gordon when he left, but heard that with the compensation he’d received, he’d opened a grocery store in Prescot.

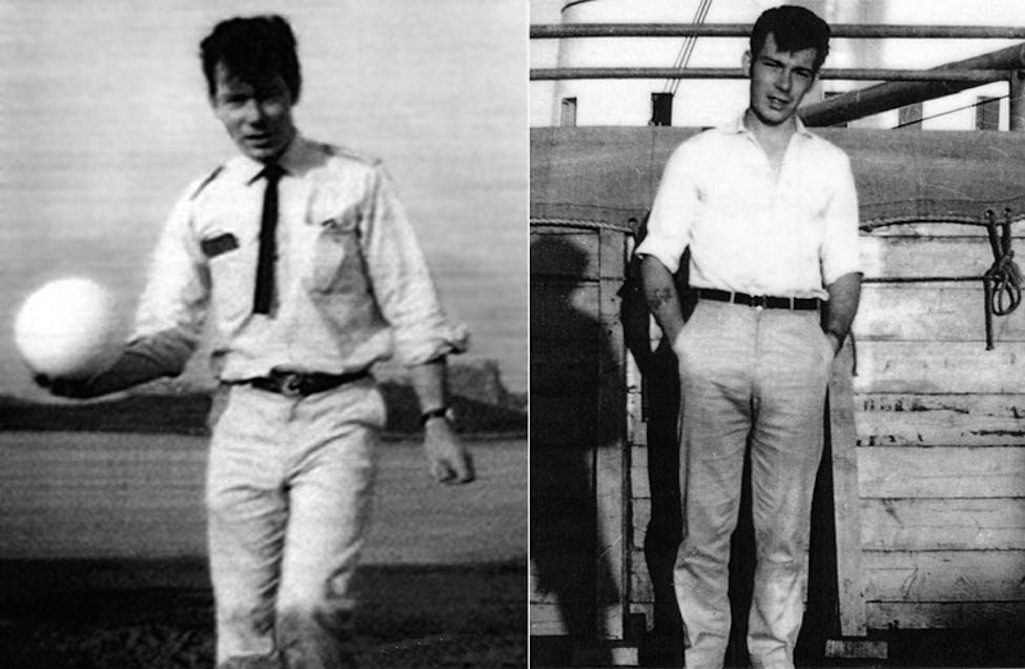

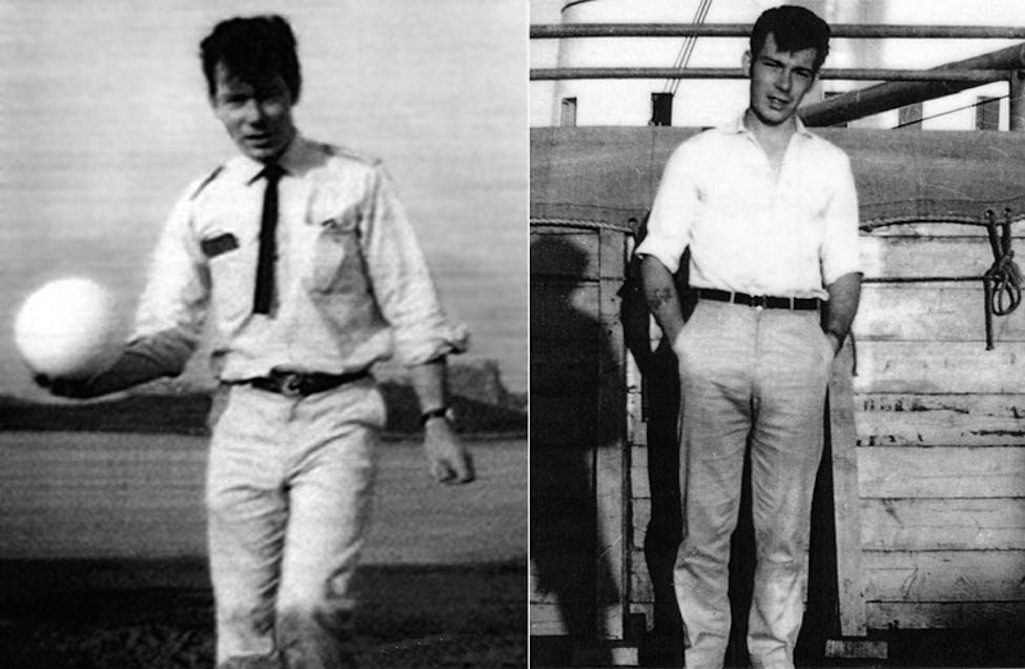

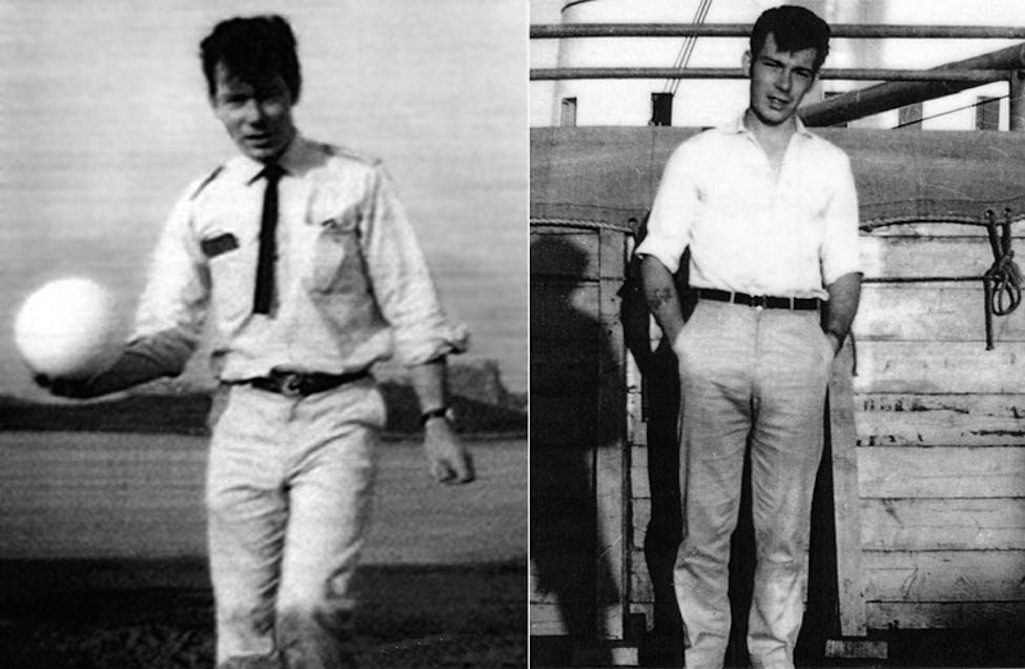

Stan on Copacabana Beach in 1964 and on the journey to Lima, Peru in 1966 - contributed by Stan Johnson

Stan on Copacabana Beach in 1964 and on the journey to Lima, Peru in 1966

Stan on Copacabana Beach in 1964 and on the journey to Lima in 1966

But the memories of my days down Sutton Manor will always be with me, as I have just written them. I hope that some miners of that time are reminded of the way things used to be and will always remember it as not just a workplace, but as a place of excitement and danger with memories to hang onto.